Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Update

March 15, 2016

Reprints

Author

Ralph J. Panos, MD, Chief of Medicine, Cincinnati Veteran Affairs Medical Center; Professor of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH.

Peer Reviewer

Hemant Shah, MD, FACP, FCCP, DSM, Associate Professor of Medicine, Wright State University-Boonshoft School of Medicine; Medical Director, CCU, Kettering Medical Center; Medical Director, Respiratory Care, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH.

Statement of Financial Disclosure

To reveal any potential bias in this publication, and in accordance with Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines, we disclose that Dr. Farel (CME question reviewer) owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Stapczynski (editor) owns stock in Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AxoGen. Dr. Wise (editor) reports he is on the speakers bureau for the Medicines Company. Dr. Schneider (editor), Dr. Panos (author), Dr. Shah (peer reviewer), Ms. Coplin (executive editor), Mr. Springston (associate managing editor), Ms. Mark (executive editor), and Mr. Landenberger (editorial and continuing education director) report no financial relationships relevant to this field of study.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has a range of extra-pulmonary complications that contribute to significant morbidity.

- Titrate oxygen therapy to maintain SaO2 between 88% and 92% when treating acute COPD exacerbations.

- Initial treatment for COPD exacerbations includes inhaled bronchodilators (beta-agonsist with or without anticholinergics) and oral corticosteroids.

- Administer systemic antibiotics in COPD patients who are being admitted, especially if going to the ICU or receiving mechanical ventilation.

- Initiate noninvasive ventilation in the ED for patients with acute respiratory failure who are not responding to inhaled bronchodilators and systemic corticosteroids.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic, incurable but very treatable condition. Currently, COPD is the third leading cause of death in the United States and has been diagnosed in nearly 10% of adult Americans. This syndrome is identified by historical clues, clinical signs and symptoms, and physiologic and imaging abnormalities. There is no single diagnostic test for COPD.

DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION

COPD is a treatable, usually preventable, and, most frequently, insidiously progressive lung disease characterized by physiologic airflow limitation and/or radiographic imaging evidence of emphysema with pulmonary and systemic inflammation and a clinical course that is punctuated by exacerbations and episodes of worsening respiratory symptoms.1-4 Over the past decade, this definition of COPD has changed dramatically, as have the characterization and treatment of individuals with COPD. Multiple new therapies alter the course of this disease, reduce exacerbations, improve quality of life, and increase survival.

Traditionally, COPD has been considered an overlapping of two principle conditions: emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Emphysema is defined histopathologically or radiographically by the loss of lung parenchyma and abnormal enlargement of air spaces without associated fibrosis, whereas chronic bronchitis is defined clinically as the presence of a productive cough for at least three consecutive months in two consecutive years. Over the past decade, further refinements in the constellations of symptoms defining various groups of patients with COPD have been developed. These clinical groupings have been called COPD phenotypes and they are believed to assist with the prediction of clinical course and optimal therapies (see Table 1).

TABLE 1. COPD PHENOTYPES

|

COPD Phenotype |

Treatment |

|||||

SABA |

LABA+/or LAMA |

ICS |

Mucolytic |

Macrolide |

PDE4 Inhibitor |

|

|

Overlap asthma/COPD |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||

|

Non- or infrequent exacerbator |

+ |

+ |

||||

|

Frequent exacerbator |

||||||

|

Emphysema |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||

|

Phlegm- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Use of COPD phenotypes to guide COPD treatment Abbreviations: SABA: short-acting beta-agonist; LABA: long-acting beta-agonist; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; PDE4: phosphodiesterase 4 |

||||||

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Estimates of COPD’s prevalence range from 6.8% to 9.4% of the U.S. adult population and vary based on the criteria used to define COPD and the objective measurement of airflow limitation.5,6 By 2008, lower respiratory diseases, including COPD, were the third-leading cause of death in the United States.7

In early COPD, the major causes of death are lung cancer and cardiac disease, whereas in more advanced COPD, respiratory failure is the major cause of mortality.8,9 During acute exacerbations of COPD, the leading causes of death are heart failure (37.2%), pneumonia (27.9%), pulmonary thromboembolism (20.9%), and respiratory failure (14%).10

RISK FACTORS FOR COPD

The single most significant risk factor for the development of COPD is tobacco smoke inhalation. Factors that influence the development of COPD include the age of starting smoking, amount and type of tobacco product consumed, age of quitting, and length of smoking cessation.11 The prevalence of COPD has generally followed the prevalence of tobacco smoking, with a lag time of approximately 20-30 years. Whereas only 20-50% of all smokers develop COPD, approximately 75-90% of all individuals with COPD have been or are smokers. Approximately one-quarter of individuals with COPD are never smokers.12,13 Other factors that may be associated with the development of COPD include indoor and outdoor air pollution; occupational exposures to gases, dusts, and fumes; and respiratory infections such as tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus.12,14-21 In the developing world, exposure to biomass smoke is a leading cause of COPD.22-24

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Pulmonary. Breathlessness, cough, and sputum production are the three major symptoms of COPD. Dyspnea is a subjective sensation of lack of air that is normally experienced by everyone during vigorous or strenuous activity; when shortness of breath impedes routine activity, it suggests a transition from a normal physiological response to a symptom of a pathologic process. Breathlessness may progress insidiously in individuals with COPD. Initially, there may be subtle changes such as an inability to maintain the pace when walking with peers or increased sensation of breathing while doing routine activities, which gradually progresses to impede routine daily activities. Cough is the forceful exhalation of air to clear the airways from irritating or obstructing material. Cough may be nonproductive or productive of phlegm.

The differential diagnosis of COPD includes other pulmonary processes, such as asthma, bronchiolitis, pulmonary infections, bronchiectasis, and cardiac disorders, including ischemic heart disease and congestive heart failure. In some patients it may not be possible to distinguish asthma and COPD despite extensive evaluation, and this undifferentiated group is now classified as the asthma COPD overlap syndrome (see Table 1).

Extra-pulmonary Manifestations. Over the past decade, COPD has been recognized to be more than just a pulmonary disorder. Inflammation is postulated to be the pathophysiologic process linking pulmonary and nonpulmonary manifestations of COPD.25-33 This multisystemic involvement is believed to be due to inflammatory cytokines produced within the lungs and released into the circulation or inflammatory cells that are activated within the lungs and then enter the circulation for distribution throughout the body.34 These nonpulmonary manifestations include cardiac, cerebrovascular, oncologic, musculoskeletal, hematologic, endocrine, and psychologic disorders.

The prevalence of ischemic cardiovascular disease among individuals with COPD is more than twice the level found among smokers who do not have COPD.35,36 It is estimated that cardiovascular mortality increases by 28% for every 10% decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1).37 More than one-quarter of patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations have elevations in serum markers of cardiac ischemia and approximately 8% have myocardial infarctions.38 This increased risk of cardiac ischemia may be due to elevated inflammatory cytokines that can increase the risk of plaque rupture, demand ischemia caused by an increased heart rate due to the underlying pulmonary disease, hypoxemia, and beta-agonist and anti-cholinergic medication effects.39,40

Between 9% and 52% of individuals with COPD have heart failure, and co-existent COPD and heart failure are associated with greater mortality than either process alone.41,42 Due to similarities in the clinical presentation of heart failure and COPD exacerbations, there may be a tendency to treat a patient for both processes simultaneously. However, mortality and hospitalizations are increased for patients with left ventricular heart failure but not COPD who are treated with beta-agonists.43 However, beta-blocker treatment for individuals with COPD and congestive heart failure should be continued during hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations and is considered to be safe chronically.44

Approximately one in four smokers with obstructive lung disease will develop lung cancer, whereas cancer is only predicted to occur in one of every 14 smokers who do not have airflow limitation.45 Radiographic evidence of emphysema increases the risk for lung cancer by 3.5-fold.46 In addition, concurrent COPD predicts a worse course for lung cancer patients.47

In contrast with popular belief, the most common hematologic manifestation of COPD is anemia (7.5-32.7%) and not polycythemia (6%).48-53 COPD-related anemia is usually associated with a normal to low mean corpuscular volume, low serum iron, and normal to increased ferritin.54 It is postulated to be caused by chronic inflammation (anemia of chronic disease). Patients with anemia generally have more breathlessness, decreased exercise capacity, lower quality of life, and increased health care utilization and cost.49-52,55-59

Approximately 24-69% of individuals with COPD have osteoporosis, 27-67% have osteopenia, and 24-63% have vertebral fractures.60-66 Vertebral fractures may cause kyphosis that further impairs lung function; for every vertebral fracture, the forced vital capacity (FVC) may be reduced by 9%.67 In addition, the presence of COPD predicts an increased risk of hip fracture, and nearly half of all individuals with hip fractures have COPD.68,69

Both the prevalence and risk of developing diabetes are increased in individuals with COPD.35,70,71 This increased prevalence and incidence of diabetes is greater than would be expected with corticosteroid use. Concurrent diabetes increases the risk for hospitalization and death among individuals with COPD.72-74

Nocturnal respiratory symptoms, intrinsic sleep-disordered breathing, or a combination of both of these processes contribute to sleep disturbances in 32-78% of patients with COPD. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) occurs in approximately 10% of individuals with COPD, and the concurrence of OSA and COPD is known as the overlap syndrome. Risk factors for the overlap syndrome include obesity and, possibly, more severe airflow limitation. The combined effects of OSA and COPD cause profound nocturnal desaturation, which may contribute to the development of severe pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary vascular disorders occur frequently in individuals with COPD. Up to 25% of patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations have venous thromboembolism, which may increase morbidity and mortality and precipitate pulmonary hypertension.

Thus, nonpulmonary processes cause significant morbidity and mortality in COPD. Increased awareness, detection, and management of these manifestations of COPD have the potential to improve survival, reverse morbidity, improve quality of life, and reduce healthcare utilization among patients with COPD. At present, there is no evidence that current pharmacologic treatments for COPD are effective treatments for COPD’s nonpulmonary manifestations.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Spirometry. Because COPD is a syndrome, there is not a single objective criterion for its diagnosis. Although pulmonary physiologic measurement of airflow limitation was previously required for the diagnosis of COPD and remains the most commonly applied diagnostic standard, recent evidence shows that some individuals with radiographic evidence of emphysema may not have demonstrable obstruction during spirometric testing.75 Therefore, physiologic demonstration of obstruction is a critical but not essential factor in the diagnosis of COPD, especially emphysema.

Spirometry is an effort-dependent test that measures the amount of air expelled from the lungs over time. Reproducibility and testing accuracy are dependent on well-trained personnel who are able to coach patients to provide maximal effort during testing. During testing, the patient breathes in maximally to total lung capacity and then quickly exhales down to residual volume, sustaining the exhalation for 6 seconds and the volume of air expelled from the lungs is measured.

The two key spirometric measurements are the amount of air expelled in the first second (FEV1), and the total amount of air exhaled (FVC). The spirometer also calculates the FEV1:FVC ratio, which is used to diagnose airflow obstruction or limitation. Normally, this ratio is approximately 80% (four-fifths of a vital capacity can be exhaled within the first second of exhalation). With obstruction, the FEV1:FVC ratio is reduced. The two most common thresholds for the definition of airflow limitation are an absolute value of FEV1/FVC < 0.7 or the lower limit of normal, the fifth percentile of the distribution of the FEV1/FVC ratio in a nonsmoking population with no clinical evidence of lung disease. As individuals age, the ratio of FEV1:FVC decreases.

Imaging. The most common imaging tests for the evaluation of COPD are the chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT) scan (see Figures 1, 2, and 3). Common chest radiographic manifestations of COPD include lung hyperinflation that manifests as enlarged lung fields, flattened diaphragms (best seen on the lateral view), increased retrosternal airspace, and caudal movement of the mediastinum with inferior displacement of the heart. Emphysema may cause effacement of the vascular markings and cause cysts or bullae. CT scans are more sensitive than chest radiographs for detecting the presence of emphysema and may be used to quantify lung parenchymal destruction, air trapping, and hyperinflation.76,77 CT scans are also useful in the diagnosis of bronchiectasis and, more recently, have been used to measure airway luminal diameter and wall thickness that may be increased in chronic bronchitis.78-80

FIGURES 1 and 2. POSTERIOR-ANTERIOR AND LATERAL CHEST X-RAYS

FIGURE 3. CHEST COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY SCAN (UPPER, MIDDLE, AND LOWER LUNG ZONES)

This chest CT scan is from the same patient whose chest X-ray is presented in Figure 1. The chest CT shows diffuse emphysema with loss of lung parenchyma.

There is a calcified nodule in the posterior left lower lobe

MANAGEMENT OF STABLE COPD

The goals of COPD treatment include reduction in respiratory symptoms, improved quality of life, preservation of lung function, reduced COPD-associated complications and comorbidities, decreased number and severity of COPD exacerbations, and improved survival.

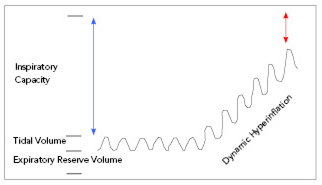

In the past decade, multiple COPD treatments have been demonstrated to improve longevity (see Table 3). The principle clinical manifestation of COPD is breathlessness that initially occurs only with exertion and eventually progresses to interrupt daily activities. Causes of dyspnea may be multifactorial with contributions from bronchospasm, oxygen desaturation, secretions, and cough, but the major factor contributing to breathlessness is dynamic lung hyperinflation. Lung hyperinflation is caused by an increase in the volume of air remaining in the lungs at the end of a normal exhalation (end expiratory lung volume [EELV]) that causes excessive stretch and distension (loading) of the respiratory muscles, placing them at a mechanical disadvantage precipitating the sensation of breathlessness. In COPD, air is easily inhaled but exhalation is impaired; if less air is exhaled than is inhaled, hyperinflation occurs and EELV increases. With each breath, the EELV increases and eventually impairs the ability to inhale due to restriction of the inspiratory capacity and decreasing minute ventilation. The respiratory rate increases during exertion and there is less time in exhalation, which further worsens hyperinflation (see Figure 4). Bronchodilators may reduce dynamic hyperinflation, but the best approach is to maintain a slow and steady respiratory pattern by inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth with pursed lips. This technique, which is called pursed lip breathing, elevates the intra-airway pressure and maintains airway patency by reducing collapse due to reduced elastic recoil. By maintaining airway patency during exhalation, more air is expelled, less dynamic hyperinflation occurs, and breathlessness is alleviated.

TABLE 2. COPD SEVERITY BASED ON FEV 1 PERCENT PREDICTED

FEV 1 Percent Predicted |

COPD Severity |

|

≥ 80% |

Mild |

|

< 80% and ≥ 50% |

Moderate |

|

< 50% and ≥ 30% |

Severe |

|

< 30% |

Very severe |

TABLE 3. EVIDENCE-BASED INTEREVENTIONS TO REDUCE MORTALITY IN COPD

COPD Treatments that Improve Survival |

|

Smoking cessation |

|

Oxygen for patients with resting hypoxemia |

|

Influenza vaccination |

|

Noninvasive ventilation for respiratory failure |

|

Pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise |

|

Tiotropium |

|

Lung volume reduction surgery in selected patients |

FIGURE 4. DYMANIC HYPERINFLATION

Dynamic hyperinflation is the major cause of breathlessness in individuals with COPD. In COPD, air is easily inhaled but exhalation is impeded by airflow limitation caused by increased resistance and reduced elastic recoil; if less air is exhaled than was inhaled, the lung begins to retain air, increasing the end expiratory lung volume (EELV). As EELV increases, the volume of air inhaled during subsequent breaths is decreased due to restriction of the inspiratory capacity. Thus, the lungs are unable to meet ventilatory and oxygenation demands. The increase in respiratory rate that occurs with exertion further augments hyperinflation by reducing expiratory time, causing more air trapping and increase in the EELV. As hyperinflation increases, the respiratory muscles are stretched or loaded causing discomfort; the stretching also causes functional weakness by putting the muscles at a mechanical disadvantage. The discomfort caused by stretching and loading of respiratory muscles by dynamic hyperinflation is a significant factor contributing to the sensation of breathlessness. Both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments may help to ameliorate dynamic hyperinflation. Pursed lip breathing facilitates exhalation of air by creating an increased expiratory resistance that elevates the intra-airway pressure to maintain airway patency, reducing collapse due to diminished elastic recoil and increasing the amount of air expelled during exhalation. The improved expiratory airflow reduces air trapping and hyperinflation. Slow, deliberate, and controlled breathing utilizing pursed lip breathing helps to reduce the respiratory rate, which increases the exhalation time that may also reduce air trapping and hyperinflation. Control of anxiety, relaxation techniques, and better awareness of the perception of breathlessness may also help reduce the rate of breathing. |

The mainstays of COPD pharmacologic management are bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids. Short-acting beta-agonists are usually the initial bronchodilator and should be prescribed on an as-needed basis as a rescue inhaler. The next level pharmacologic treatment is the addition of a long-acting anticholinergic or long-acting beta-agonist. Nebulizers are an alternative to metered-dose inhalers when patients are unable to use metered-dose inhalers properly or when they are hospitalized.

Other medications for the treatment of COPD include phosphodiesterase inhibitors, macrolides, and mucolytics. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors include methylxanthines such as theophylline or aminophylline, which are rarely used due to their narrow therapeutic window and frequent side effects and medication interactions. The specific phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, roflumilast, is approved by the FDA for the reduction of COPD exacerbations in individuals with chronic bronchitis and frequent exacerbations.81 Macrolides, such as erythromycin and azithromycin, have anti-inflammatory properties in addition to antimicrobial effects. Recent studies have shown that either daily erythromycin or azithromycin decreases the frequency of COPD exacerbations in patients with a history of exacerbations.82-84

Mucolytics such as n-acetylcysteine and carbocysteine may reduce COPD exacerbations and improve health-related quality of life in patients with COPD.85 In one prospective study, n-acetylcysteine reduced hyperinflation.86 Mucolytics are used more frequently in Europe than in the United States.

Supplemental oxygen improves survival in patients with hypoxemia at rest (PaO2 < 55 torr or SpO2 < 88%; or PaO2 < 60 and > 55 torr with evidence of cor pulmonale).87,88 The mechanism(s) by which supplemental oxygen improves mortality is unknown.

Smoking cessation is the singularly most important intervention for the prevention and treatment of COPD. Even after initially quitting, many smokers return to smoking. Half of all individuals who are able to quit smoking for at least 6 months will resume smoking within 8 years of quitting.89 Thus, the process of smoking cessation is often a series of episodes of quitting and relapse before permanent abstinence is achieved.

Most COPD management guidelines recommend both influenza and pneumococcal vaccination for individuals with COPD. Influenza vaccination reduces mortality, outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and exacerbations.90 Although pneumococcal vaccination reduces the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease, it has not shown any significant effect on mortality, rates of pneumonia or exacerbations, lung function, or cost effectiveness.90,91 Vaccination against both influenza and pneumococcus may reduce COPD exacerbations more effectively than either vaccine alone.90

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a multidisciplinary program of education and exercise that provides COPD patients with information about their disease, its treatment, and mechanisms to cope with its consequences. Pulmonary rehabilitation is most effective when it is integrated into a comprehensive COPD management program that encourages behavior change and a shift from provider-initiated to patient self-directed care.

Surgical or endoscopic lung volume reduction may also be effective in certain patients with COPD. Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) removes emphysematous lung parenchyma, which allows less deranged lung tissue to ventilate more normally, improving overall lung function. LVRS improves exercise tolerance, quality of life, and survival in selected patients with COPD.92 However, this surgery is only beneficial in patients with upper lobe emphysema and poor exercise tolerance and is detrimental in individuals with FEV1 < 20% of predicted, diffusing capacity < 20% of predicted, or diffusely distributed emphysema.

EVALUATION OF APPARENT COPD EXACERBATIONS

The course of COPD is often marked by intermittent exacerbations and episodes of increased respiratory symptoms (especially cough, wheezing, phlegm production, and breathlessness) that vary in severity, frequency, duration, and consequence. A COPD exacerbation is defined as an acute event characterized by worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variations and leads to a change in medication.1

Risk factors for COPD exacerbations include age, worse quality of life, severity of airflow limitation (reduction in FEV1), chronic bronchitis, and comorbidities (especially gastroesophageal reflux disease).93 The best predictor of future exacerbations is a history of prior exacerbations.94

Between 70-80% of COPD exacerbations are triggered by viral and bacterial respiratory infections and the majority of the rest are due to environmental exposures such as air pollution and medication non-adherence.95,96

The symptoms of a COPD exacerbation depend on its cause. Typical manifestations include cough, sputum production, dyspnea, tachypnea, wheezing, and a decrease in pulmonary function. Physical examination findings depend on the severity of the exacerbation and typically include tachypnea and wheezing. In more severe exacerbations, patients develop difficulty speaking, use accessory respiratory muscles, and exhibit paradoxical chest and abdominal wall movements due to asynchrony between the chest and abdomen during breathing. In very severe exacerbations, patients may develop hypoxemia and hypercapnia with lethargy and possibly obtundation.

Assessment of the COPD patient who presents with worsening respiratory symptoms should consider a differential diagnosis that includes congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pneumothorax, and pulmonary thromboembolism, as well as an apparent COPD exacerbation. The medical history and physical examination are the initial steps by which possibilities are considered and excluded. In most moderate to severe apparent COPD exacerbations, ancillary tests are necessary (see Table 4).

TABLE 4. RECOMMENDED ANCILLARY TESTS IN COPD EXACERBATIONS

Test |

Rationale |

|

Pulse oximetry |

To identify arterial hypoxemia and guide oxygen therapy |

|

Venous blood gas |

A normal PvCO2 excludes arterial hypercarbia |

|

Electrocardiogram |

To detect occult myocardial ischemia and correctly identify tachycardic rhythms |

|

Chest radiograph |

To detect infiltrates or pneumothorax not detectable on lung examination |

|

Brain natriuretic peptide |

To identify coexisting heart failure |

|

Cardiac troponin |

To detect occult cardiac ischemia |

|

D-dimer |

To detect potential venous thromboembolism |

|

CBC and metabolic panel |

To assess general hematologic, metabolic, renal, and hepatic function and identify chronic metabolic alkalosis (elevated serum bicarbonate) in response to chronic respiratory acidosis (pCO2 retention) |

|

Procalcitonin |

To differentiate bacterial from nonbacterial processes and to provide support for the de-escalation/stoppage of antibiotics |

Pulse oximetry is universally routine to adult emergency department (ED) patients. In the COPD patient, pulse oximetry is used to guide oxygen therapy (see section on ED Management of COPD Exacerbations). Some COPD patients are chronically hypoxemic, so values obtained in the ED should be compared with their baseline to identify deterioration. Simiarly, ventilatory failure with carbon dioxide retention or hypercarbia is a potential complication indicating the potential for further deterioration. However, some patients with COPD chronically retain carbon dioxide, and it is essential to differentiate acute from chronic and acute on chronic carbon dioxide retention. In these cases, determination of the arterial blood pH is key; respiratory acidemia is often due to an acute or acute on chronic disorder. Another clue is the serum bicarbonate; a value greater than 28-29 mmol/L suggests a chronic metabolic alkalosis in compensation for chronic respiratory acidosis due to long-standing carbon dioxide retention. An arterial blood gas measurement is the traditional approach to detect carbon dioxide retention, but is uncomfortable and carries a small risk of complications. To reduce pain with arterial blood gas sampling, apply an ice bag for 3 minutes to the radial artery puncture site97 and use a 23g needle to shorten the duration of the procedure.98 An alternative to arterial sampling is to measure venous carbon dioxide (PvCO2); a value within normal range excludes arterial hypercarbia.99

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is considered routine in acute COPD exacerbations. It is useful to identify myocardial ischemia and evaluate tachycardias. As opposed to asthma exacerbations in which routine chest radiography is unnecessary, a chest radiograph should be obtained in all cases of COPD exacerbation. The physical examination has limited accuracy in excluding pneumonia or pneumothorax in COPD patients.

As noted earlier, COPD patients have an increased risk for heart failure, and heart failure exacerbations may mimic or be coincident with COPD exacerbations. The serum levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) may be slightly elevated in patients with COPD exacerbations, reflecting cardiac stress,100 but elevated levels (> 100 pg/mL) can be used to identify coexisting heart failure.101

Detecting myocardial ischemia in a COPD exacerbation patient may be difficult. The pain from ischemic myocardium may be obscured by symptoms of breathlessness and mechanical chest wall pain due to increased work of breathing. Characteristic ECG manifestations of myocardial ischemia may not be as readily apparent due to concurrent pulmonary and pulmonary vascular ECG findings. Thus a low threshold for obtaining cardiac biomarkers is recommended.

Pulmonary embolism can occur coincident with or mimic a COPD exacerbation. The reported frequency with which this occurs varies widely, depending on enrollment criteria and extent of evaluation.102-110 (See Table 5.) While the incidence is low in patients who are only treated in the ED, it increases among those patients who require hospitalization and for whom no apparent cause of COPD exacerbation is identified.

TABLE 5. REPORTED INCIDENCE OF PULMONARY EMBOLISM IN APPARENT COPD EXACERBATIONS

Author |

Country |

Setting |

Number of Patients |

DVT Incidence |

PE Incidence |

|

NR = not reported |

|||||

|

Shapira-Rootman (2015)102 |

Israel |

Hospitalized |

49 |

NR |

9 (18%) |

|

Bahloul (2014)103 |

Tunisia |

ICU |

131 |

NR |

23 (17.5%) |

|

Akpinar (2014)104 |

Turkey |

Hospitalized |

172 |

50 (29.1%) |

50 (29.1%) |

|

Choi (2013)105 |

Korea |

Hospitalized |

102 |

6 (6%) |

5 (5%) |

|

Dutt (2011)106 |

India |

Hospitalized |

100 |

9 (9%) |

2 (2%) |

|

Gunen (2010)107 |

Turkey |

Hospitalized |

131 |

14 (10.6%) |

18 (13.7%) |

|

Rutschmann (2007)108 |

Switzerland |

ED |

123 |

2 (1.6%) |

4 (3.3%) |

|

Tillie-Leblond (2006)109 |

France |

Hospitalized |

197 |

NR |

49 (25%) |

|

Mispelaere (2002)110 |

France |

Hospitalized |

31 |

6 (19%) |

9 (29%) |

While a serum d-dimer is sensitive for venous thromboembolism in COPD patients, there is reduced specificity with standard cutoff values (500 ng/mL). To improve specificity, there is the suggestion that a higher d-dimer threshold should be used in COPD exacerbations to reduce CT pulmonary angiogram imaging.111 Until replicated, it is prudent to stick with the most common threshold used in the literature, 500 ng/mL, and image those with values above this threshold.

ED MANAGEMENT OF COPD EXACERBATIONS

In the last decade, an evidence-based approach to the management of COPD exacerbations has evolved (see Table 6).112,113 The strength with which each treatment can be recommended is assessed by the quality and quantity of supporting data. Level A evidence is derived from large randomized, controlled trials that show consistent benefit in the appropriate patient population. Level B evidence is also based on randomized trials, but with a smaller number of patients (the result of subgroup or post-hoc analysis) the study population differs from the target group, and/or the results are somewhat inconsistent. Level C evidence is derived from uncontrolled, nonrandomized, or observational cohort studies. Level D evidence is developed from expert consensus opinions.

TABLE 6. EVIDENCE-BASED MANAGEMENT OF COPD EXACERBATIONS

Agent |

Rationale |

Strength of Evidence |

|

Supplemental oxygen to maintain SaO2 between 88% and 92% |

Hypoxemia is a stress on vital organs, but administering oxygen to elevate SaO2 above 92% is harmful. |

B |

|

Inhaled short-acting bronchodilators |

Improves symptoms and airflow (FEV1) |

C |

|

Systemic corticosteroids |

Shortens recovery time, improves airflow (FEV1) and arterial hypoxemia Reduces the rates of treatment failure and early relapse |

A B |

|

Intravenous methylxanthines |

Second-line therapy when insufficient response to inhaled bronchodilators and systemic corticosteroids |

B |

|

Systemic antibiotics |

Reduces short-term mortality and treatment failure in hospitalized patients |

B |

|

Noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure |

Improves respiratory acidosis, decreases breathlessness, reduces intubation rates, and decreases short-term mortality |

A |

Supplemental oxygen is reflexively applied to almost all ED patients in respiratory distress. This reflex is to be avoided, as prehospital and ED studies have shown supplemental oxygen is harmful in COPD exacerbations if treatment results in hyperoxia (SaO2 > 96%).114,115 In the prehospital study from 2010, high-flow oxygen (8-10 L/min via a non-rebreather face mask) administered to patients with COPD exacerbations was associated with an in-hospital mortality of 9%, whereas oxygen administered via nasal cannula titrated to achieve an SaO2 between 88% and 92% had an observed mortality of 2%.114 The ED study from 2012 found that hyperoxemia (SaO2 > 96%) and hypoxemia (SaO2< 88%) in patients with COPD exacerbations were associated with increased incidence of serious adverse outcomes (odds ratios of 9.17 and 2.16, respectively) when compared to patients receiving oxygen titrated to maintain SaO2 between 88% and 92%.115 An often overlooked cause of hyperoxygenation is the use of high-flow oxygen to power nebulizers; compressed air should be used with nebulizers to prevent complications of oxygen-induced hypoventilation. Thus, oxygen is beneficial in controlled amounts.

Inhaled short-acting bronchodilators are the principle pharmacologic treatments for acute COPD exacerbations and consist of both beta adrenergic agonists and anticholinergic agents. Albuterol is the most frequently used beta adrenergic agonist and may be delivered by metered-dose inhaler (MDI) or nebulization. Both of these delivery methods provide equivalent drug delivery and clinical effectiveness, but both clinicians and patients seem to prefer nebulization due to perceived ease of use. Typical albuterol dosing is 2.5 mg by nebulizer or 4-8 puffs (90 mcg per puff) by MDI and spacer every 1-4 hours. Continuous albuterol nebulizer treatments or increased frequency does not improve lung function or clinical outcome but may cause excessive tachycardia, tremors, or hypokalemia.116 Ipratropium bromide is the most frequently used short-acting anticholinergic agent and the usual dose is 500 mcg by nebulizer or 2-4 puffs (18 mcg/puff) by MDI with spacer every 4-6 hours. There is conflicting evidence about the efficacy of combined beta adrenergic agonists and anticholinergic agents; earlier studies showed an additive bronchodilator effect but no clinical benefit, whereas more recent studies showed no additive bronchodilation.117,118 Further, the dosing interval for the two medications is quite different: short-acting beta-agonists every 1-4 hours and short-acting anticholinergics every 4-6 hours. More frequent use of short-acting anticholinergics in combination preparations may lead to increased adverse effects.

Short-acting bronchodilators are continued as long as the patient has evidence of respiratory distress. There is no evidence from which to recommend a specific mode (intermittent vs continuous dose), duration, or frequency for short-acting bronchodilator therapy in COPD exacerbations. The intensity of inhaled bronchodilator therapy is sometimes limited by adverse side effects. There is no advantage to using intravenous beta-agonists in COPD exacerbations.

Systemic corticosteroids are useful in COPD exacerbations; they improve airflow, arterial hypoxemia, and shorten recovery time (level A). There is also evidence they reduce the rates of treatment failure (defined as the need for mechanical ventilation) and short-term relapse (level B). There are not many studies that can be used to identify the ideal dose and duration. Clinical experience (level B) is that a dose of prednisone 40 mg per day for 5 days is both safe and effective.113 Although very often the initial corticosteroid dose is given intravenously in COPD exacerbations, there is no evidence that this is superior to the oral route.119 In non-critically ill patients, 5 days of therapy produces the same outcome benefit as 14 days.120 In critically ill patients, there is no evidence that very large doses, > 240 mg/day of methylprednisolone, are better than smaller doses.121 In summary, for non-critically ill patients with COPD exacerbations, use oral prednisone 40 mg per day for 5 days. For critically ill patients, keep the daily dose to less than 240 mg methylprednisolone IV per day.

Methylxanthines (theophylline and aminophylline) have a modest and inconsistent effect in COPD exacerbations.122 Randomized trials of methylxanthines for exacerbations of COPD have been small and have produced conflicting results. Potential benefits of methylxanthines on lung function, clinical outcomes, and symptoms were generally not confirmed at standard levels of significance.122,123 The important adverse events of nausea and vomiting were significantly increased in patients receiving methylxanthines. Thus, these agents are recommended only if there is an inadequate response to inhaled bronchodilators and systemic corticosteroids.113

Since a portion of COPD exacerbations are due to bacterial infection, systemic antibiotics would appear to be beneficial in those patients.112,113 The challenge has been to identify which patients are likely to benefit. There is evidence to support the use of antibiotics when the COPD exacerbation is accompanied by increasing sputum purulence.113 A meta-analysis of antibiotics for COPD exacerbations found a reduction in treatment failure and mortality in hospitalized patients, with a larger benefit for more ill patients admitted to the ICU.124 For patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations, initiation of antibiotics in the first or second day was associated with a reduction in treatment failure, intubation rate, inpatient mortality, and 30-day readmission rate.125,126 In summary, initiate systemic antibiotics in the ED for patients being admitted with COPD exacerbations, especially if going to the ICU or requiring mechanical ventilation.

There is no strong evidence to recommend a specific antibiotic. In most cases, initial empirical treatment with aminopenicillin with or without clavulanic acid, macrolide, or tetracycline is reasonable.113 Where possible, the drug should be administered orally. The duration of treatment is recommended to be 5-10 days (level D). There is less evidence for antibiotic therapy for COPD exacerbations not admitted to the hospital, so antibiotic selection and duration of therapy should err on the side of caution, choosing an agent with a low incidence of adverse side effects or drug interactions and a short duration of treatment.

Serum procalcitonin should be evaluated in patients with COPD exacerbations; elevation of procalcitonin levels suggests bacterial infection and can be used to guide the duration of antibiotic use. Discontinuation of antibiotics for patients who do not have elevated procalcitonin levels reduces antibiotic exposure, cost, and emergence of resistant organisms and does not adversely affect morbidity or mortality.127

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is very beneficial in COPD patients with acute respiratory failure admitted to the hospital. In randomized trials, NIV was considered successful in 80-85% of patients where used.128 NIV improves the patient’s feeling of breathlessness and decreases respiratory rate while also lowering arterial carbon dioxide. NIV reduces the incidence of endotracheal intubation (number needed to treat [NNT] = 4), and because there is less invasive mechanical ventilation, there is a lower occurrence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. NIV improves in-hospital mortality (NNT = 10-11) and shortens hospital length of stay by up to 3 days.128,129

The indications for NIV are respiratory acidosis (pH < 7.35 and/or PaCO2 > 45 mmHg) and/or severe dyspnea with signs of respiratory fatigue or increased work of breathing. Maintain a low threshold to utilize and initiate in the ED, as early intervention likely improves outcomes. Use the respiratory therapist’s expertise to initiate treatment and adjust settings. Monitor the patient closely with repeat arterial blood gas measurements (30-60 minutes after initiation or change in NIV settings).

DISPOSITION

The decision to hospitalize an individual with a COPD exacerbation is individualized and based on the available hospital and community resources and the individual’s familial and social support network. Home care services, such as hospital in home, are able to provide equivalent outcomes as hospitalization for COPD exacerbation with significant cost savings.128

Hemodyamic or respiratory instability, alterations in mentation, cyanosis or new oxygen requirement, failure of outpatient management, severe airflow limitation, frequent exacerbations, significant comorbidities, and inadequate familial or social support network are potential indications for hospitalization. The next decision is whether a patient with a COPD exacerbation can be managed best on a medical ward or requires intensive care admission. Potential indications for critical care include life-threatening hemodynamic or respiratory instability, profound hypoxemia or hypercarbia associated with respiratory acidemia, requirement for ventilatory assistance with NIV or mechanical ventilation, and altered mentation.

CONCLUSION

COPD is a chronic, incurable but very treatable condition that is currently the third leading cause of death in the United States. COPD is a syndrome composed of historical factors, clinical signs and symptoms, and physiologic and imaging abnormalities. Classically, COPD has been classified as emphysema, chronic bronchitis, or a mixed process; more recent studies suggest that there are many more clinical groupings or phenotypes that may have prognostic and therapeutic implications. Additionally, COPD is now recognized to be a multisystemic disorder with a myriad of nonpulmonary manifestations, including cardiovascular, hematologic, endocrine, metabolic, and psychosocial derangements. Although there is no single diagnostic test for COPD, most individuals with COPD have airflow obstruction on spirometric testing and exhibit lung parenchymal and airway abnormalities on radiographic imaging. Over the past decade, the treatment of COPD has migrated from therapeutic nihilism to multiple effective medications that reduce respiratory symptoms, improve quality of life, and improve survival.

REFERENCES

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Revised 2014. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Available at: www.goldcopd.org.

- World Health Organization. Crhonic respiratory diseases. Available at: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/definition/en/.

- American Thoracic Society. Standards for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with COPD. Available at: http://www.thoracic.org/copd-guidelines/resources/copddoc.pdf.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE; American College of Physicians; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:179-191.

- Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1683-1689.

- Ford ES, Croft JB, Mannino DM, et al. Chest 2013;144: 284-305.

- Miniño AM, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Preliminary data for 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports 2010;59. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_02.pdf.

- Sin DD, Anthonisen NR, Soriano JB, Agusti AG. Eur Respir J 2006;28:1245-1257.

- Mannino DM, Doherty DE, Sonia Buist A. Respir Med 2006;100:115-122.

- Zvezdin B, Milutinov S, Kojicic M, et al. Chest 2009;136: 376-380.

- Forey BA, Thornton AJ, Lee PN. BMC Pulm Med 2011;11:36.

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Lancet 2009;374:733-743.

- Zeng G, Sun B, Zhong N. Respirology 2012;17:908-912.

- Blanc PD, Iribarren C, Trupin L, et al. Thorax 2009;64:6-12.

- Eisner MD, Anthonisen N, Coultas D, et al; Committee on Nonsmoking COPD, Environmental and Occupational Health Assembly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182: 693-718.

- Doney B, Hnizdo E, Syamlal G, et al. J Occup Environ Med 2014;56:1088-1093.

- Omland O, Würtz ET, Aasen TB, et al. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40:19-35.

- Allwood BW, Myer L, Bateman ED. Respiration 2013;86:76-85.

- Ehrlich RI, Adams S, Baatjies R, Jeebhay MF. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15: 886-891.

- Raynaud C, Roche N, Chouaid C. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:1145-1154.

- Gingo MR, Morris A, Crothers K. Clin Chest Med 2013;34:273-282.

- Regalado J, Perez-Padilla R, Sansores R, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:901-905.

- Rinne ST, Rodas EJ, Bender BS, et al. Respir Med 2006;100:1208-1215.

- Grigg J. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009;6:564-569.

- Cavaillès A, Brinchault-Rabin G, Dixmier A, et al. Eur Respir Rev 2013;22:454-475.

- Albu A, Fodor D, Poanta L, et al. Rom J Intern Med 2012;250:129-134.

- Huertas A, Palange P. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2011;5:217-224.

- Nussbaumer-Ochsner Y, Rabe KF. Chest 2011;139:165-173.

- Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1165-1185.

- Decramer M, Rennard S, Troosters T, et al. COPD 2008;5:235-256.

- Agustí A. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2007;4:522-525.

- Agusti A, Soriano JB. COPD 2008;5:133-138.

- Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghé B, et al. Eur Respir J 2008;31:204-212.

-

Agustí A, Barberà JA, Wouters EF, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:

1396-1406. - Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holquin F. Eur Respir J 2008;32:962-969.

- Finkelstein J, Cha E, Scharf SM. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2009;4:337-349.

- Sin DD, Man SF. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005;2:8-11.

- McAllister DA, Maclay JD, Mills NL, et al. Eur Respir J 2012;39:1097-1103.

- Harvey KL, Hussain A, Maddock HL. Toxicol Sci 2014;138:457-467.

- Visca D, Aiello M, Chetta A. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:184678.

- Hawkins NM, Petrie MC, Jhund PS, et al. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:130-139.

- Hawkins NM, Virani S, Ceconi C. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2795-2803.

- Au DH, Udris EM, Fan VS, et al. Chest 2003;123:1964-1969.

- Stefan MS, Rothberg MB, Priya A, et al. Thorax 2012;67:977-984.

- Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Christmas T, et al. Eur Respir J 2009;34:380-386.

- Smith BM, Pinto L, Ezer N, et al. Lung Cancer 2012;77:58-63.

- Kiri VA, Soriano J, Visick G, Fabbri L. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:57-61.

- Yohannes AM, Ershler WB. Respir Care 2011;56:644-652.

- Cote C, Zilberberg MD, Mody SH, et al. Eur Respir J 2007;29:923-929.

- Chambellan A, Chailleux E, Similowski T. ANTADIR Observatory Group. Chest 2005;128:1201-1208.

- Shorr AF, Doyle J, Stern L, et al. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1123-1130.

- Nowinski A, Kaminski D, Korzybski D, et al. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2011;79:388-396.

- Portillo K, Martinez-Rivera C, Ruiz-Manzano J. Int J Clin Pract 2013;67:558-565.

- Kollert F, Tippelt A, Müller C, et al. Respir Care 2013;58:1204-1212.

- Halpern MT, Zilberberg MD, Schmier JK, et al. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2006;4:17.

- Barba R, de Casasola GG, Marco J, et al. Curr Med Res Opin 2012;28:617-622.

- Martinez-Rivera C, Portillo K, Munoz-Ferrer A, et al. COPD 2012;9:243-250.

- Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005-1012.

- Boutou AK, Stanopoulos I, Pitsiou GG, et al. Respiration 2011;82:237-245.

- Jorgensen NR, Schwarz P, Holme I, et al. Respir Med 2007;101:177-185.

- Nuti R, Siviero P, Maggi S, et al. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:989-998.

- Papaioannou A, Parkinson W, Ferko N, et al. Osteoporos Int 2003;14:913-917.

- McEvoy CE, Ensrud KE, Bender E, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157(3 Pt 1):704-709.

- Graat-Verboom L, Wouters EF, Smeenk FW, et al. Eur Respir J 2009;34:209-218.

- Lehouck A, Boonen S, Decramer M, Janssens W. Chest 2011;139:648-657.

- Rittayamai N, Chuaychoo B, Sriwijitkamol A. J Med Assoc Thai 2012;95:1021-1027.

- Leech JA, Dulberg C, Kellie S, et al. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:68-71.

- Regan EA, Radcliff TA, Henderson WG, et al. COPD 2013;10:11-19.

- Díez-Manglano J, López-García F, Barquero-Romero J, et al; en nombre de los investigadores del estudio ECCO y del Grupo de Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna. Rev Clin Esp 2011;211:443-449.

- Laghi F, Adiguzel N, Tobin MJ. Eur Respir J 2009;34:975-996.

- Feary JR, Rodrigues LC, Smith CJ, et al. Thorax 2010;65:956-962.

- Burt MG, Roberts GW, Aguilar-Loza NR, et al. Intern Med J 2013;43:721-724.

- Parappil A, Depczynski B, Collett P, Marks GB. Respirology 2010;15: 918-922.

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. N Engl J Med 2011;364:829-841.

- Coxson HO, Leipsic J, Parraga G, Sin DD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:135-144.

- Friedman PJ. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:494-500.

- Takahashi M, Fukuoka J, Nitta N, et al. Int J COPD 2008;3:193-204.

- Nakano Y, Wong JC, de Jong PA, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:142-146.

- Patel BD, Coxson HO, Sreekumar GP, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:500-505.

- Lutey BA, Conradi SH, Atkinson JJ, et al. Chest 2013;143:1321-1329.

- Reid DJ, Pham NT. Ann Pharmacother 2012;46:521-529.

- Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, Albert R. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008;3:331-350.

- Seemungal TA, Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:1139-1147.

- Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al; COPD Clinical Research Network. N Engl J Med 2011;365:689-698.

- Decramer M, Janssens W. Eur Respir Rev 2010;19:134-140.

- Stav D, Raz M. Chest 2009;136:381-386.

- Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Ann Intern Med 1980;933:391-398.

- Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet 1981;18222:681-686.

- Yudkin P, Hey K, Roberts S, et al. BMJ 2003;327:28-29.

- Varkey JB, Varkey AB, Varkey B. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2009;15:90-99.

- Walters JA, Smith S, Poole P, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;11:CD001390.

- Tidwell SL, Westfall E, Dransfield MT. South Med J 2012;105:56-61.

- Miravitlles M, Guerrero T, Mayordomo C, et al. Respiration 2000;67:495-501.

- Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1128-1138.

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2355-2365.

- Ling SH, van Eeden SF. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2009;4:233-243.

- Haynes JM. Respir Care 2015;60:1-5.

- Patout M, Lamia B, Lhuillier E, et al. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139432.

- Foex BA. Emerg Med J 2015;32:251-253.

- Nishimura K, Nishimura T, Onishi K, et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:155-162.

- Buchan A, Bennett R, Coad A, et al. Open Heart 2015;2:e000052.

- Shapira-Rootman M, Beckerman M, Soimu U, et al. Emerg Radiol 2015;22:257-260.

- Bahloul M, Chaari A, Tounsi A, et al. Clin Respir J 2015;9:270-277.

- Akpinar EE, Hoşgün D, Akpinar S, et al. J Bras Pneumol 2014;40:38-45.

- Choi KJ, Cha SI, Shin KM, et al. Respiration 2013;85:203-209.

- Dutt TS, Udwadia ZF. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2011;53:207-210.

- Gunen H, Gulbas G, In E, et al. Eur Respir J 2010;35:1243-1248.

- Rutschmann OT, Cornuz J, Poletti PA, et al. Thorax 2007;62:121-125.

- Tillie-Leblond I, Marquette CH, Perez T, et al. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:390-396.

- Mispelaere D, Glerant JC, Audebert M, et al. Rev Mal Respir 2002;19:415-423.

- Akpinar EE, Hoşgün D, Doğanay B, et al. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:430-434.

- Qureshi H, Sharafkhaneh A, Hanania NA. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2014;5:212-227.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Available at:http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2015_Sept2.pdf.

- Austin MA, Wills KE, Blizzard L, et al. BMJ 2010 Oct 18;341:c5462.

- Cameron L, Pilcher J, Weatherall M, et al. Postgrad Med J 2012;88:684-689.

- Nair S, Thomas E, Pearson SB, et al. Chest 2005;128:48-54.

- O’Driscoll BR, Taylor RJ, Horsley MG, et al. Lancet 1989;1:1418-1420.

- McCrory DC, Brown CD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4)(4):CD003900.

- Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, et al. JAMA 2010;303:2359-2367.

- Leuppi JD, Schuetz P, Bingisser R, et al. JAMA 2013;309:2223-2231.

- Kiser TH, Allen RR, Valuck RJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:1052-1064.

- Barr RG, Rowe BH, Camargo CA Jr. BMJ 2003;327:643.

- Duffy N, Walker P, Diamantea F, et al. Thorax 2005;60:713-717.

- Vollenweider DJ, Jarrett H, Steurer-Stey CA, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD010257.

- Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, et al. JAMA 2010;303:2035-2042.

- Stefan MS, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, et al. Chest 2013;143:82-90.

- Schuetz P, Muller B, Christ-Crain M, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD007498.

- Ram FS, Picot J, Lightowler J, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD004104.

- Stefan MS, Nathanson BH, Higgins TL, et al. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1386-1394.

COPD is a chronic, incurable but very treatable condition. This syndrome is identified by historical clues, clinical signs and symptoms, and physiologic and imaging abnormalities.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.