Teen Pregnancy Part 2: Obstetrical Complications in Adolescents

October 1, 2020

Reprints

AUTHORS

Lauren B. Querin, MD, MS, Medical Education Fellow, Clinical Instructor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Daniel Migliaccio, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

PEER REVIEWER

Catherine Marco, MD, Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wright State University, Dayton, OH

Executive Summary

• Fetal viability is considered at approximately 22-24 weeks’ gestation (fundal height at least at or above the umbilicus).

• Pregnant trauma patients ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation can develop a condition called supine hypotension syndrome, secondary to the inferior vena cava being compressed by a gravid uterus while the mother is lying supine. This can be improved by positioning the mother in the left lateral decubitus position whenever possible.

• As soon as maternal resuscitation allows, all pregnant women at ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation presenting with trauma should have cardiotocographic and fetal heart rate monitoring started and continued for a minimal period of four to six hours, even if the patient is asymptomatic.

• Trauma imaging should be obtained based on traumatic indications and should not be withheld simply due to pregnancy. The risk of missed or delayed diagnosis of traumatic injury outweighs the risk of fetal exposure to ionizing radiation.

• Gestational hypertension is a new onset of elevated blood pressure (systolic pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg) after 20 weeks’ gestation without proteinuria or other signs of end-organ damage.

• Pulmonary embolism is the leading cause of maternal death in the United States. The occurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnancy is 10 times that of the general population.

• Pregnancy-specific VTE risk factors include grand multiparity, age > 35 years, obesity, hyperemesis, bed rest for more than four days, and preeclampsia.

• Treatment of VTE in pregnancy should begin with stabilization (airway, breathing, and circulation) and determination of whether the patient has cardiovascular compromise severe enough to be life-threatening, requiring potential thrombolytic therapy or percutaneous or surgical intervention. If acutely stable, therapeutic anticoagulation is indicated, with low molecular-weight heparin (e.g., enoxaparin) being the first-line medication.

• Postpartum hemorrhage occurs in approximately 4% to 6% of all pregnancies, with uterine atony the most common etiology.

• Perform an exam to identify the cause of the hemorrhage (e.g., boggy uterus suggestive of uterine atony vs. bleeding laceration from birth trauma). If the exam is consistent with uterine atony, or no other clear source of traumatic etiology is identified, the next step is to administer oxytocin (Pitocin), either intravenously or intramuscularly, and perform bimanual uterine massage.

Teen pregnancies are at high risk of obstetrical complications with an increased rate of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Acute care clinicians should be familiar with, and adept at, caring for the common or emergent obstetrical complications that may occur in a pregnant teenager.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

Introduction

Despite a recent decline in teen birth rates in the United States, adolescent pregnancy rates remain high when compared to other developed countries.1,2 There are many unique barriers and considerations when diagnosing and caring for pregnant patients of adolescent age, many of which are discussed in depth in “Teen Pregnancy Part 1.” (See Pediatric Emergency Medicine Reports, September 2020.) This article will focus on the medical adverse outcomes and obstetrical complications that can occur in adolescent pregnancy. Topics include trauma in pregnancy; preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome; venous thromboembolism; as well as precipitous delivery and postpartum hemorrhage.

Trauma in Pregnancy

A 17-year-old female, gravidity 1, parity 0, at 33 weeks’ gestation arrives to the emergency department via emergency medical services after being involved in a motor vehicle crash. The patient was the restrained driver of a vehicle that was rear-ended at approximately 20 miles per hour. She had no loss of consciousness, self-extricated, and was ambulatory on the scene. Her vital signs are within normal limits. She is complaining of mild abdominal pain and cramping without vaginal bleeding or leakage of fluid. She reports normal fetal movement.

Trauma is the number one cause of nonobstetrical, pregnancy-associated maternal death in the United States.3 The most common causes of trauma include motor vehicle collisions (accounting for 50% of pregnancy-related trauma), falls, and assault.4 Complications of trauma during pregnancy include preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, placental abruption, fetal maternal hemorrhage, uterine rupture, and fetal demise. It is important to note that some of these complications, particularly placental abruption, can occur with even minor maternal injuries.5

During evaluation and resuscitation of a pregnant trauma patient, maternal resuscitation always takes priority because fetal survival is dependent on maternal survival. Fetal viability is considered at approximately 22-24 weeks’ gestation (fundal height at least at or above the umbilicus).

The initial approach to a pregnant trauma patient should follow the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines. However, there are additional considerations in the evaluation and treatment of pregnant women presenting with trauma. Unique anatomic and physiologic changes of pregnancy can affect trauma resuscitation and care.

- Pregnancy results in a relative hypervolemic state with an increase in cardiac output of 30% to 50%. Therefore, clinically significant injuries can be easily masked. With this, uterine injury can result in significant maternal hemorrhage, given the substantial increase in uterine blood flow during pregnancy.6 When giving a crystalloid infusion, consider increasing the volume administered by 50%.

- In addition, pregnant trauma patients can develop a condition called supine hypotension syndrome. At ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation, the inferior vena cava can be compressed by a gravid uterus while the mother is lying supine. That can decrease venous return and cardiac output, leading to hypotension. This can be improved by positioning the mother in the left lateral decubitus position whenever possible.6

- The diaphragm can elevate by up to 4 cm during pregnancy. This is important to keep in mind during chest tube insertion. Additional physiologic respiratory changes during pregnancy include a decrease in functional residual volume and in partial pressure of carbon dioxide, making respiratory compensation more difficult. It is important to keep in mind that if intubation is indicated, pregnant women often will become hypoxic more quickly during the apneic period.6 They also typically are at higher risk of aspiration given delayed gastric emptying and upward displacement of intra-abdominal organs during pregnancy.

After a standard primary survey per the ATLS protocol, unique adjuncts of a secondary trauma survey in a pregnant patient include an assessment of fetal heart tones and uterine size, as well as a thorough abdominal and genitourinary examination to assess for uterine tenderness, ecchymosis, and vaginal bleeding. As soon as maternal resuscitation allows, all pregnant women at ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation presenting with trauma should have cardiotocographic and fetal heart rate monitoring started and continued for a minimal period of four to six hours, even if the patient is asymptomatic.5,7 If there are any signs of fetal distress (late decelerations, persistent tachycardia, or bradycardia), admission for monitoring for a minimum of 24 hours is indicated. Additionally, an obstetrical ultrasound should be performed to assess for fetal size/gestational age, fetal cardiac activity, and fetal movement.

Regarding other trauma imaging, imaging should be obtained based on traumatic indications and should not be withheld simply due to pregnancy. The risk of missed or delayed diagnosis of traumatic injury outweighs the risk of fetal exposure to ionizing radiation.8 Indications for emergent laparotomy or other trauma surgery monitoring/interventions should remain the same as in nonpregnant patients.

Other therapeutic considerations should include tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis prophylaxis if there has been no booster in the past five years, as well as administration of Rho(D) immunoglobulin (Rhogam) in all Rhesus-negative patients.9

Traumatic Placental Abruption

Placental abruption can occur with even seemingly minor trauma in pregnant women ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation.10 This is in part because, with trauma, there is a sudden stretching of the underlying uterine wall that can cause shearing stress on an inelastic placenta. Continuous fetal monitoring for signs of uterine irritability (three or more contractions in one hour) or fetal distress is essential. Note that although placental abruption can be diagnosed via obstetrical ultrasound, the sensitivity for this method is exceedingly low (25%), making it an unreliable test to rule out placental abruption in trauma.11

Typical symptoms of placental abruption include uterine contractions or back pain with vaginal bleeding. The uterus often is firm, and contractions typically are high-frequency but low-amplitude.12 Note that blood loss may be underestimated due to the possibility of blood retention behind the placenta. In some cases, patients will have no vaginal bleeding at all.

Placental abruptions result in significantly increased morbidity and mortality for both the mother and the fetus via an increased risk of maternal disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and fetal-maternal hemorrhage.13 If there is concern for a severe traumatic mechanism, DIC laboratory tests (coagulation profile with fibrinogen) and a Kleihauer-Betke test (quantifies the presence of fetal hemoglobin in maternal circulation) could be obtained. If there are concerns for maternal or fetal compromise, an obstetrical evaluation is emergently indicated, as delivery may be imminent.

Traumatic Arrest and Perimortem Cesarean Delivery

A perimortem cesarean delivery is defined as a cesarean delivery performed during active or imminent maternal cardiac arrest. The primary goal is to resuscitate the mother, while the secondary goal is to potentially improve fetal viability. Although the traditional indication for perimortum cesarean delivery was a gestational age of 24 weeks or older, most recommendations now state that it should be considered in any patient whose uterine fundus can be palpated at the umbilicus or above, with the presumption that this makes the gestational age at least 20 weeks.14

In addition to gestational age, a perimortem cesarean delivery should be performed within four minutes of maternal arrest.15 Although not a comprehensive description, the following are some key features of the perimortem cesarean delivery technique.6

- The physician performing the procedure should be the physician with the most surgical experience whenever possible.

- Using a No. 10 blade, an initial incision should be made beginning from the xiphoid process (or at least from the level of the uterine fundus) and extending inferiorly to the pubic symphysis.

- Once through the subcutaneous tissue to the peritoneum, an incision through the peritoneum should be made using either a scalpel or scissors to deliver the uterus.

- Then, a midline vertical incision should be made on the lower portion of the uterus while taking caution to avoid the placenta, bowel, or bladder.

- Once in the uterine cavity, the physician should digitally separate the uterine wall away from the fetus. Then, the incision can be extended with scissors superiorly until the baby is exposed.

- The cord then should be clamped and cut, and infant resuscitation should begin.

- Simultaneously, the uterine and abdominal cavity should be packed to limit further bleeding while continued maternal resuscitation efforts are made.

- If return of spontaneous circulation is obtained, further surgical closure should be continued in the operating room, and the mother should receive broad-spectrum prophylactic antibiotics.

Preeclampsia, Eclampsia, and HELLP Syndrome

A 15-year-old female, gravidity 1, parity 0, at 36 weeks’ gestation, presents to the emergency department with a headache for the past two days. The headache is diffuse and has progressively worsened. It is associated with blurred vision. She denies any fevers, vomiting, or head trauma as well as any contractions, vaginal bleeding, or leakage of fluid. Her vital signs are temperature 36.8°C, heart rate 107 beats/minute, blood pressure 165/95 mmHg, and respiratory rate 22 breaths/minute.

Hypertensive disorders complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies worldwide.16 By definition, gestational hypertension is a new onset of elevated blood pressure (systolic pressure

≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg) after 20 weeks’ gestation without proteinuria or other signs of end-organ damage.17 This patient would meet criteria for severe gestational hypertension, which is defined as a systolic pressure

≥ 160 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 110 mmHg.

In a newly hypertensive pregnant patient, a key goal in the initial evaluation is to determine the correct diagnosis: gestational hypertension, severe gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP syndrome. Each of these diagnoses involves a different course of management and prognosis. See Table 1 for terminology definitions.

Table 1. Terminology: Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy19,20 |

|

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Chronic hypertension |

|

|

Gestational hypertension |

|

|

Severe gestational hypertension |

|

|

Preeclampsia |

|

|

Preeclampsia with severe features |

|

|

Eclampsia |

|

|

Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) |

|

Some of these conditions are considered to exist on a spectrum and often can progress to a more severe condition over time. For example, 10% to 50% of women diagnosed with gestational hypertension will go on to develop preeclampsia within a few weeks of initial diagnosis. Then, preeclampsia with severe features can develop rapidly over a period of days.18

It is important for emergency department providers to be able to distinguish between chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia without severe features, where patients can be discharged with close follow-up and outpatient management, vs. preeclampsia with severe features, eclampsia, and HELLP, which require emergent actions.

Emergency Department Workup for a Hypertensive Pregnant Patient

If the patient is otherwise stable (i.e., no seizure-like activity, respiratory distress, altered mental status, hemodynamic instability, etc.), the initial step is to obtain a thorough history, including gravidity and parity numbers, prior pregnancy complications, previous medical history and medications, gestational age, and presence of symptoms. Specifically, it is important to ask whether the patient has had any symptoms that would be concerning for the diagnosis of preeclampsia with severe features. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Severe Features Associated with Preeclampsia17 |

|

Systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure |

|

New-onset cerebral or visual disturbance

|

|

Severe, persistent right upper quadrant or epigastric abdominal pain not accounted for by alternative diagnosis |

|

Serum transaminase ≥ two times the upper limit of normal |

|

Platelet count < 100,000 platelets per microliters |

|

Renal insufficiency (creatinine |

|

Pulmonary edema |

On physical examination, providers should assess for crackles, bilateral lower extremity edema, or signs of respiratory distress that would be concerning for a fluid overload status with pulmonary edema. The examination also should include a neurologic examination, including reflexes, and an abdominal examination to assess for right upper quadrant (RUQ) tenderness.

Laboratory workup includes complete blood count (to assess for anemia or thrombocytopenia), basic metabolic panel (for serum creatinine), liver function tests (to assess for transaminitis), urinalysis (to assess for proteinuria), urine protein/creatinine ratio, uric acid, and lactate dehydrogenase (elevated levels are associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes).21, 22

See Table 3 for a summary of how to treat and manage various pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders.22-26

Table 3. Emergency Department Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy22-26 |

|

|

Hypertensive Disorder |

Treatment |

|

Preeclampsia without severe features |

|

|

Preeclampsia with severe features |

|

|

Eclampsia |

|

|

HELLP syndrome |

|

|

Key: OB: obstetrical/obstetrician; IV: intravenous; BP: blood pressure; ABCs: airway, breathing, circulation; RSI: rapid sequence intubation; |

|

Venous Thromboembolism in Pregnancy

A 15-year-old female, gravidity 1, parity 0, at 33 weeks’ gestation presents with sudden-onset, sharp, left-sided chest pain and shortness of breath beginning five hours prior to arrival. She states that she has had intermittent dyspnea gradually worsening over the past few weeks and worsening acutely today. She has had no abdominal pain, contractions, or vaginal bleeding. Vital signs are temperature 37.4°C, heart rate 108 beats/minute, blood pressure 110/78 mmHg, and respiratory rate 26 breaths/minute.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the leading cause of maternal death in the United States.27 The occurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnancy is 10 times that of the general population. Evaluation of VTE in pregnancy is further complicated by the fact that symptoms concerning for VTE also are often common signs and symptoms of normal pregnancy (e.g., dyspnea, tachycardia, and/or lower extremity swelling).28 Additionally, traditional diagnostic testing for pulmonary embolism poses higher risks to the fetus, which further complicates the VTE workup in pregnancy.

Pregnant women meet all three of Virchow’s triad for VTE, including hypercoagulation, vascular damage, and venous stasis.29 Pregnancy-specific VTE risk factors include grand multiparity, age > 35 years, obesity, hyperemesis, bed rest for more than four days, and preeclampsia.30 It is important to note that women remain at higher risk of VTE for more than eight weeks postpartum.

Signs and symptoms of VTE are similar in pregnant and nonpregnant individuals. For deep vein thrombosis (DVT), one would expect to see asymmetric extremity swelling (typically lower extremities) and pain. Of note, the majority of DVTs are left-sided (90%).31 For PE, symptoms vary from mild dyspnea and tachypnea to full cardiopulmonary collapse.32

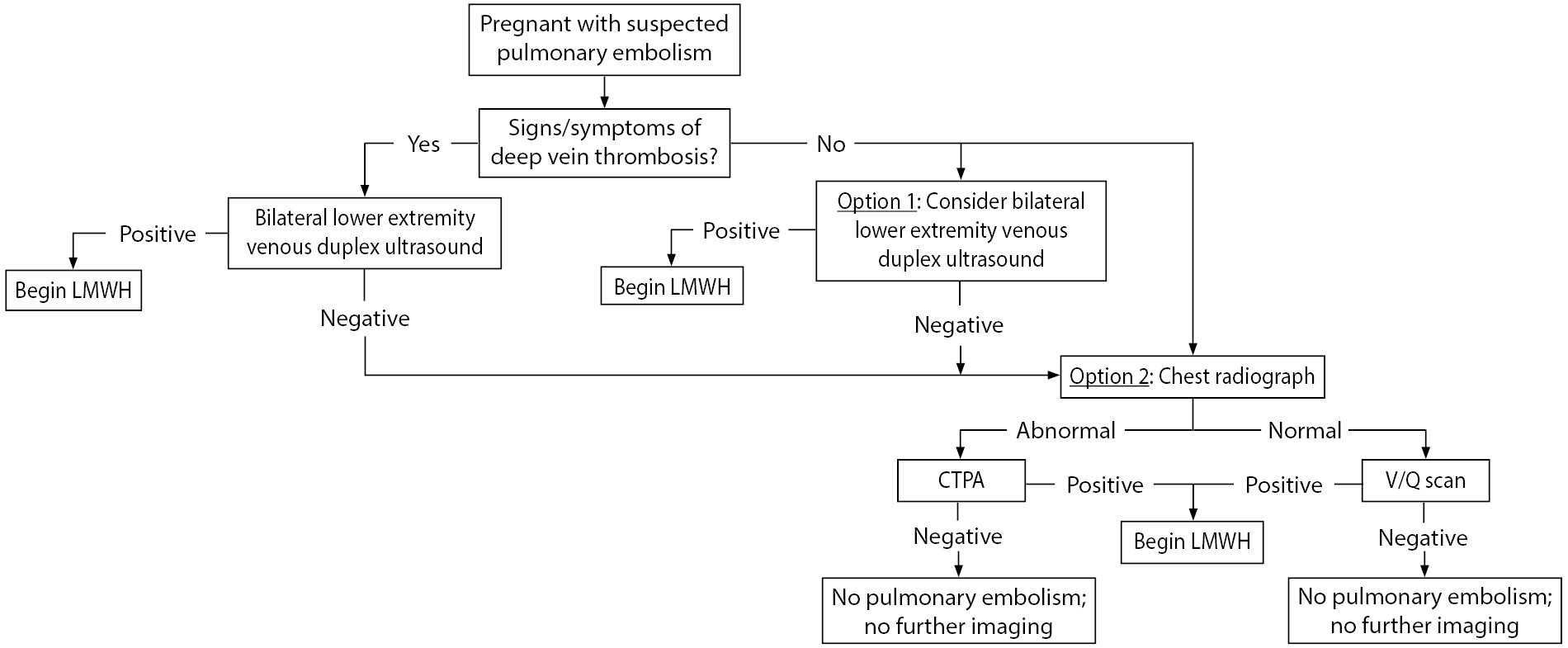

Figure 1 shows an approach to the diagnosis of VTE in pregnant patients. If there is clinical concern for DVT, clinicians should obtain compression duplex ultrasounds of the lower extremities. This diagnostic test is noninvasive, posing little risk to the fetus without exposure to radiation, and has a sensitivity of 89% to 96%.33,34 If the presentation is concerning for PE, some would recommend starting with bilateral lower extremity compression duplex ultrasounds, even in patients without the clinical signs of DVT. Given that treatment would be the same for both conditions, clinicians should stop further diagnostic workup if duplex ultrasounds are positive for DVT, therefore minimizing radiation exposure to the mother and fetus.35

Figure 1. Diagnostic Approach to Venous Thromboembolism in Pregnancy |

|

|

Key: LMWH: low molecular-weight heparin; CTPA: computed tomography pulmonary angiogram; V/Q: ventilation perfusion |

In nonpregnant women, a D-dimer often is used as a screening test for patients who are otherwise low-risk for VTE. However, D-dimer levels are elevated in normal pregnancies and gradually increase with gestational age and into the postpartum period. Therefore, they are not as reliable as screening tools.

A 2019 study by Van der Pol et al proposed the YEARS algorithm, which used three criteria (clinical signs of DVT, hemoptysis, and PE as the most likely diagnosis), plus a D-dimer for the diagnostic evaluation of PE in pregnant women.36 The authors concluded that PE was safely ruled out by the pregnancy-adapted YEARS algorithm and that chest computed tomography (CT) was avoided in a large cohort of patients (32% to 65%). However, external validation of this study is still needed. Therefore, use of D-dimer for diagnostic evaluation of PE in pregnancy remains controversial.

A chest X-ray can be obtained prior to more invasive tests, as it can rule out other pathologies (e.g., pneumonia, pneumothorax), and, if abnormal, may increase or decrease clinical suspicion for PE. Abnormal features that could be attributed to PE include atelectasis, pulmonary edema, pleural effusions, and focal opacities.37

The decision to proceed with a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) vs. a ventilation perfusion (V/Q) scan is multifactorial, including availability, institutional guidelines, and clinician preference. However, studies have shown that CTPA typically is the diagnostic study of choice in patients who have abnormal findings on chest radiography.38

It is important to note that both CTPA and V/Q scans carry similar fetal radiation exposure risks (~0.5 mGy) and that one study exposes a fetus to well below the threshold for fetal malformation related to radiation (threshold 100-200 mGy).39

Treatment of VTE in pregnancy should begin with stabilization (airway, breathing, and circulation) and determination of whether the patient has cardiovascular compromise severe enough to be life-threatening, requiring potential thrombolytic therapy or percutaneous or surgical intervention. If acutely stable, therapeutic anticoagulation is indicated, with low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) (e.g., enoxaparin) being the first-line medication.34,40,41 Therapeutic anticoagulation should be continued for a minimum of three to six months and at least until six weeks postpartum.34

Precipitous Delivery and Postpartum Hemorrhage

A 16-year-old female, gravidity 1, parity 0, at 40 weeks’ gestation presents by emergency medical services with strong uterine contractions reported to be two to three minutes apart. The patient is in obvious distress and states that she feels like she needs to push. On genitourinary examination, the infant’s head is visible at the vaginal introitus.

Emergency medicine clinicians also should be prepared in the case of a precipitous vaginal delivery. Precipitous labor is defined as labor that lasts less than three hours from onset of contractions to completion of delivery.42 Women presenting in precipitous labor typically have had little or no prenatal care and, therefore, the neonates are more likely to be premature or have higher-risk features.43

When a woman presents in precipitous labor, if delivery is not immediately imminent, clinicians should obtain a brief history, including questions regarding gestational age, number of babies expected to be delivered, when contractions began and how far apart they are, leakage of fluid from the vagina, fetal movement, and any complications with the current or past pregnancies. While there are numerous possible maternal or fetal complications, the vast majority of precipitous deliveries presenting to the emergency department occur without complication. While all peripartum complications cannot be discussed in detail here, further details regarding postpartum hemorrhage (one of the most common and life-threatening complications of childbirth) are described later.

Uncomplicated Delivery of the Newborn

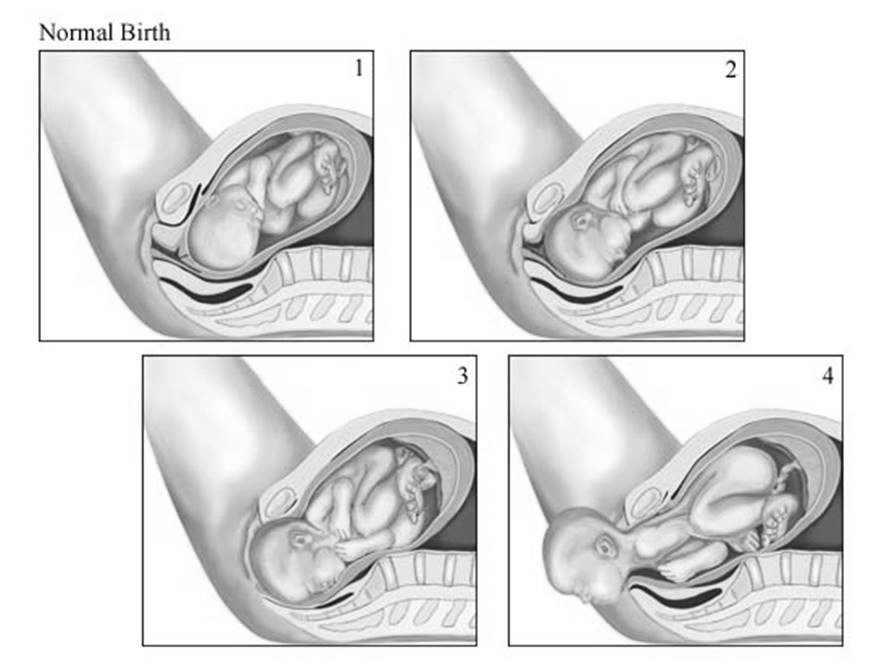

Physical delivery of the newborn as the baby passes through a completely dilated cervix through the birth canal is known as the second stage of labor. (See Figure 2.) During this time, it is the delivering clinician’s responsibility to reduce the risks of maternal trauma and neonatal injury. Multiple methods that are subtly different can be used to deliver the head of the baby. There is no true consensus regarding which method is best.44-48 One common method is the “hands on” approach, in which one hand is used to place gentle pressure of the occiput of the baby’s head through crowning while simultaneously using the thumb and index finger of the other hand to provide counter protection to the perineum.49,50

Figure 2. Delivery Process |

|

|

1. Fetal engagement begins 2. Further descent, fetal rotation begins 3. Fetal rotation completes, extension begins 4. Complete fetal extension Source: © Relias LLC 2020 |

After the fetal head has been completely delivered, allow for restitution of the fetal head (i.e., rotation of the head to where the face is oriented laterally to the right or left). After restitution, the fetal shoulders will need to be delivered. The clinician should place one hand on each side of the head and should place gentle downward traction toward the mother’s sacrum to help guide the baby’s anterior shoulder under the maternal symphysis pubis. After delivery of the anterior shoulder, the posterior shoulder can be released by then applying direct, gentle, upward traction on the baby. Once the shoulders are delivered, the remainder of the neonate’s body will easily expulse. The cord then should be clamped and cut. Finally, the third stage of labor includes delivery of the placenta.

Active management of delivery of the placenta includes beginning a uterotonic agent, typically oxytocin intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV). Then, the clinician should use one hand to apply firm, but controlled, downward traction on the transected umbilical cord while applying firm downward pressure suprapubically to prevent uterine inversion.51 After delivery of the placenta, a clinician should explore for lacerations that need repair and assess for uterine atony to help reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (discussed in more detail later).

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage occurs in approximately 4% to 6% of all pregnancies, with uterine atony the most common etiology.52

Postpartum hemorrhage is defined as blood loss of 1,000 mL or more accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia (e.g., lightheadedness, tachycardia, palpitations, hypotension) within 24 hours of giving birth.53 The initial management step for postpartum hemorrhage includes thinking about the resuscitation basics. Ensure the mother is on a monitor and has adequate vascular access (a minimum of two large-bore IV infusions).

Perform an exam to identify the cause of the hemorrhage (e.g., boggy uterus suggestive of uterine atony vs. bleeding laceration from birth trauma). If the exam is consistent with uterine atony, or no other clear source of traumatic etiology is identified, the next step is to administer oxytocin (Pitocin), either IV or IM, and perform bimanual uterine massage.

A bimanual uterine massage is performed by placing one hand inside the vagina and placing firm pressure on the uterine body with a closed fist. The other hand is placed over the uterine fundus to compress it down against the uterine body. If oxytocin and uterine massage fail to control the hemorrhage, several additional medications can be considered. Table 4 describes options for medical management of postpartum hemorrhage, the typical recommended dosages, and special considerations regarding contraindications.52,54,55

Table 4. Options for Medical Management of Postpartum Hemorrhage54-56 |

|||

|

Medication |

Dose |

Contraindications |

Adverse Effects |

|

Oxytocin |

10 units IM or 10 to 40 units per |

Possible hypotension with IV use following cesarean delivery |

Minimal; nausea or vomiting with prolonged use |

|

Methylergonovine |

0.2 mg IM taken orally every two to four hours |

Hypertension or preeclampsia; known cardiovascular disease |

Severe hypertension (especially if given intravenously), nausea, or vomiting |

|

Carboprost |

0.25mg IM or into myometrium every 15-90 minutes; max cumulative dose 2 mg |

Avoid in patients with asthma, or significant renal, hepatic or cardiac disease |

Nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, transient fever, shivering, headache, bronchospasm |

|

Misoprostol (PGE1) |

1,000 mcg rectally once; alternate dose 400 to 800 mcg saline lock |

Use cation in patients with cardiovascular disease |

Nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, transient fever, shivering, headache |

|

Tranexamic acid (TXA) |

1 g infused in 10-20 minutes |

Rare/none |

Thrombosis/venous thromboembolism |

|

IM: intramuscularly |

|||

Should the hemorrhage persist despite exhaustion of medical management, the uterus and vaginal canal should be packed, and emergent obstetrical consultation or transfer to a facility with obstetrical specialists is indicated. Additionally, for any patient with significant hemorrhage or hemodynamic instability, transfusion with blood products should be considered, beginning with packed red blood cells. Clinicians also should consider the potential need for the use of a massive transfusion protocol.

Conclusion

Teen pregnancies are at higher risk of obstetrical complications with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes than adult pregnancies in the United States.56,57 Pediatric emergency medicine clinicians should be familiar with and adept at caring for the common or emergent obstetrical complications as outlined earlier.

REFERENCES

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK. National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Reports. Births: Final data for 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports. Hyattsville; 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Health: Teen Pregnancy. Updated March 1, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm

- United Nations Statistics Division. Demographic Yearbook 2013. Published 2015.

- Lindberg LD, Santelli JS, Desai S. Changing patterns of contraceptive use and the decline in rates of pregnancy and birth among U.S. adolescents, 2007-2014. J Adolesc Health 2018;63:253-256.

- Maslowsky J, Powers D, Hendrick CE, Al-Hamoodah L. County-level clustering and characteristics of repeat versus first teen births in the United States, 2015-2017. J Adolesc Health 2019;65:674-680.

- Maravilla JC, Betts KS, Couto E, et al. Factors influencing repeated teenage pregnancy: A review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:527-545.

- Kost K, Maddow-Zimet I, Arpaia A. Pregnancies, births and abortions among adolescents and young women in the United States, 2013: National and state trends by age, race and ethnicity. Published September 2017. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/us-adolescent-pregnancy-trends-2013

- Causey AL, Seago K, Wahl NG, Voelker CL. Pregnant adolescents in the ED: Diagnosed and not diagnosed. Am J Emerg Med 1997;15:125-129.

- Fraser AM, Brockert JE, Ward RH. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:1113-1117.

- Olausson PM, Cnattingius S, Goldenberg RL. Determinants of poor pregnancy outcomes among teenagers in Sweden. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:451-457.

- Rees JM, Lederman SA, Kiely JL. Birth weight associated with lowest neonatal mortality: Infants of adolescent and adult mothers. Pediatrics 1996;98:1161-1166.

- Phipps MG, Blume JD, DeMonner SM. Young maternal age associated with increased risk of postneonatal death. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:481-486.

- Paranjothy S, Broughton H, Adappa R, Fone D. Teenage pregnancy: Who suffers? Arch Dis Child 2009;94:239-245.

- Malabarey OT, Balayla J, Klam SL, et al. Pregnancies in young adolescent mothers: A population-based study on 37 million births. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2012;25:98-102.

- Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Morisaki N, et al. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: A World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG 2014;121(Suppl 1):40-48.

- Traisrisilp K, Jaiprom J, Luewan S, Tongsong T. Pregnancy outcomes among mothers aged 15 years or less. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1726-1731.

- Brosens I, Muter J, Gargett CE, et al. The impact of uterine immaturity on obstetrical syndromes during adolescence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:546-555.

- Perper K, Peterson K, Manlove J. Child Trends. Diploma Attainment Among Teen Mothers. Washington; 2010.

- Hoffman SD, ed. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. The Urban Institute Press; 2008.

- Assini-Meytin LC, Green KM. Long-term consequences of adolescent parenthood among African-American urban youth: A propensity score matching approach. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:529-535.

- Nord CW, Moore KA, Morrison DR, et al. Consequences of teen-age parenting. J Sch Health 1992;62:310-318.

- Kingston D, Heaman M, Fell D, et al. Comparison of adolescent, young adult, and adult women’s maternity experiences and practices. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1228-e1237.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011;84:478-485.

- Shen J, Che Y, Showell E, et al. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1:CD001324.

- Committee on Adolescence. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics 2012;130:1174-1182.

- Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, et al. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: A systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1994-2000.

- Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: A randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:555-562.

- Noon B, Dixon W. Rethinking emergency contraception. EM Resident, Published April 22, 2020. https://www.emra.org/emresident/article/emergency-contraception/

- Sayle AE, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. A prospective study of the onset of symptoms of pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:676-680.

- Guttmacher Institute. An overview of consent to reproductive health services by young people. Updated July 1, 2020. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law

- Jenkins A, Millar S, Robins J. Denial of pregnancy – a literature review and discussion of ethical and legal issues. J R Soc Med 2011;104:286-291.

- Miller LJ. Psychotic denial of pregnancy: Phenomenology and clinical management. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1233-1237.

- Boyer D, Fine D. Sexual abuse as a factor in adolescent pregnancy and child maltreatment. Fam Plann Perspect 1992;24:4-11,19.

- Noll JG, Shenk CE, Putnam KT. Childhood sexual abuse and adolescent pregnancy: A meta-analytic update. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:366-378.

- Daley AM, Sadler LS, Reynolds HD. Tailoring clinical services to address the unique needs of adolescents from the pregnancy test to parenthood. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2013;43:71-95.

- Teagle SE, Brindis CD. Perceptions of motivators and barriers to public prenatal care among first-time and follow-up adolescent patients and their providers. Matern Child Health J 1998;2:15-24.

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Ugalde J, Todic J. Substance use and teen pregnancy in the United States: Evidence from the USDUH 2002-2012. Addict Bhehav 2015;45:218-225.

- Tsamantioti ES, Hashmi MF. Teratogenic medications. StatPearls. Updated Jan. 4, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553086/

- Dinwiddie KJ, Schillerstrom TL, Schillerstrom JE. Postpartum depression in adolescent mothers. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2018;39:168-175.

- Vigod SN, Dennis CL, Kurdyak PA, et al. Fertility rate trends among adolescent girls with major mental illness: A population-based study. Pediatrics 2014;133:e585-e591.

- Reese D. The mental health of teen moms matters. Seleni, Published 2018. https://www.seleni.org/advice-support/2018/3/14/the-mental-health-of-teen-moms-matters

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757: Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e208-e212.

- Everett C. Incidence and outcome of bleeding before the 20th week of pregnancy: Prospective study from general practice. BMJ 1997;315:32-34.

- Hasan R, Baird DD, Herring AH, et al. Association between first-trimester vaginal bleeding and miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:860-867.

- Hendriks E, MacNaughton H, Mackenzie MC. First trimester vaginal bleeding: Evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 2019;99:166-174.

- Connolly A, Ryan DH, Stuebe AM, Wolfe HM. Reevaluation of discriminatory and threshold levels for serum beta-hCG in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:65-70.

- Barnhart KT, Guo W, Cary MS, et al. Differences in serum human chorionic gonadotropin rise in early pregnancy by race and value at presentation. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:504-511.

- Barnhart KT. Clinical practice. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2009;361:379-387.

- Rodgerson JD, Heegaard WG, Plummer D, et al. Emergency department right upper quadrant ultrasound is associated with a reduced time to diagnosis and treatment of ruptured ectopic pregnancies. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:331-336.

- Rogers SK, Chang C, DeBardeleben JT, Horrow MM. Normal and abnormal U.S. findings in early first-trimester pregnancy: Review of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2012 Consensus Panel Recommendations. Radiographics 2015:35:2135-2148.

- Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1443-1451.

- Poulose T, Richardson R, Ewings P, Fox R. Probability of early pregnancy loss in women with vaginal bleeding and a singleton live fetus at ultrasound scan. J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;26:782-784.

- Deutchman M, Tubay AT, Turok D. First trimester bleeding. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:985-994.

- Nanda K, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2012:CD003518.

- Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Porter R, et al. Management of miscarriage: Expectant, medical, or surgical? Results of randomised controlled trial (miscarriage treatment (MIST) trial). BMJ 2006;332:1235-1240.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: Observational study. BMJ 2002;324:873-875.

- Kim C, Barnard S, Neilson JP, et al. Medical treatments for incomplete miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD007223.

- Neilson JP, Hickey M, Vazquez J. Medical treatment for early fetal death (less than 24 weeks). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2006:CD002253.

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:837-843.

- Clayton HB, Schieve LA, Peterson HB, et al. Ectopic pregnancy risk with assisted reproductive technology procedures. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:595-604.

- Ankum WM, Mol BWJ, Van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 1996;65:1093-1099.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Shojaei T, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: A comprehensive analysis based on a large case-control, population-based study in France. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:185-194.

- Mol BWJ, Ankum WM, Bossuyt PMM, Van der Veen F. Contraception and the risk of ectopic pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Contraception 1995;52:337-341.

- Cheng L, Zhao WH, Zhu Q, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: A multi-center case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:187.

- Cheng L, Zhao WH, Meng CX, et al. Contraceptive use and the risk of ectopic pregnancy: A multi-center case-control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e115031.

- Hoover RN, Hyer M, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Adverse health outcomes in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1304-1314.

- Craig LB, Khan S. Expectant management of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2012;55:461-470.

- Barash JH, Buchanan EM, Hillson C. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:34-40.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 181: Prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e57-e70.

- Goodwin TM. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2008;35:401-417, viii.

- [No authors listed]. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 153: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e12-e24.

- Whelan LJ. Chapter 99: Comorbid Disorders in Pregnancy. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Fell DB, Dodds L, Joseph KS, et al. Risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum requiring hospital admission during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107(2 Pt 1):277-284.

- Giugale LE, Young OM, Streitman DC. Iatrogenic Wernicke encephalopathy in a patient with severe hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1150-1152.

- Eroğlu A, Kürkçüoğlu C, Karaoğlanoğlu N, et al. Spontaneous esophageal rupture following severe vomiting in pregnancy. Dis Esophagus 2002;15:242-243.

- Yamamoto T, Suzuki Y, Kojima K, et al. Pneumomediastinum secondary to hyperemesis gravidarum during early pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:1143-1145.

- Friedman S, Agrawal JR. Chapter 7: Gastrointestinal & Biliary Complications of Pregnancy. In: Greenberger NJ, Blumberg RS, Burakoff R, eds. Current Diagnosis and Treatment Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Heaton HA. Chapter 98: Ectopic Pregnancy and Emergencies in the First 20 Weeks of Pregnancy. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Ahmed KT, Almashhrawi AA, Rahman RN, et al. Liver diseases in pregnancy: Diseases unique to pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:7639-7646.

- Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:775-779.

- Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol 2013;1281:3-5.

Teen pregnancies are at high risk of obstetrical complications with an increased rate of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Acute care clinicians should be familiar with, and adept at, caring for the common or emergent obstetrical complications that may occur in a pregnant teenager.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.