Congenital Anomalies: Gastrointestinal Emergencies

Core Content: Emergency Management of Congenital Anomalies

- Know the anatomy and pathophysiology relevant to emergency management of congenital anomalies

- Know the indications and contraindications for emergency management of congenital anomalies

- Plan the key steps and know the potential pitfalls in the emergency management of congenital anomalies

- Recognize the complications associated with the emergency management of congenital anomalies

Gastrointestinal Emergencies

Newborns often lose 5-10% of their body weight in the first week of life. Weight gain then occurs at a rate of about 20-30 g per day. Most newborns will regain their birth weight by 1-2 weeks of life.

Gastroesophageal Reflux

The newborn has a relatively short esophagus, and about 50% of neonates will have benign reflux after feeding. The diagnosis may be suspected from the history and observing the infant feeding in the ED. Infants with benign GERD may be educated about proper feeding positions, decreasing volume, increasing frequency of feeds, and thickening feeds with rice cereal (1 tbsp for each 1-2 ounces of formula). An upright position for at least 20 minutes after feeding is recommended. Placing the infant into a car seat immediately after eating is discouraged as this positioning places increased pressure on the stomach and may increase reflux. Medications, such as ranitidine (a histamine-2 antagonist), may be required if these measures are unsuccessful.

Pathologic reflux is more common in premature infants and infants with congenital anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract and CNS.1 These infants may present with failure to thrive, dysphagia, feeding aversion, hematemesis, irritability, opisthotonic posturing, coughing, apnea, or respiratory distress. Aspiration may result in pneumonitis, laryngospasm, or bronchospasm. Admission is recommended if the infant presents with severe symptoms such as apnea, respiratory distress, pneumonitis, or failure to thrive. An upper GI X-ray series or Ph probe is the diagnostic modality of choice.

National Guideline/Academic Resource

- http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2013/04/24/peds.2013-0421

- http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=24538

CME Question

An infant presents with frequent spitting up of formula. This has worsened over the past week, with irritability and poor feeding. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) complications include:

- Apnea.

- Failure to thrive.

- Irritability.

- Pneumonitis.

- All of the above.

Start or Resume CME Test (Opens in a new Tab/Window)

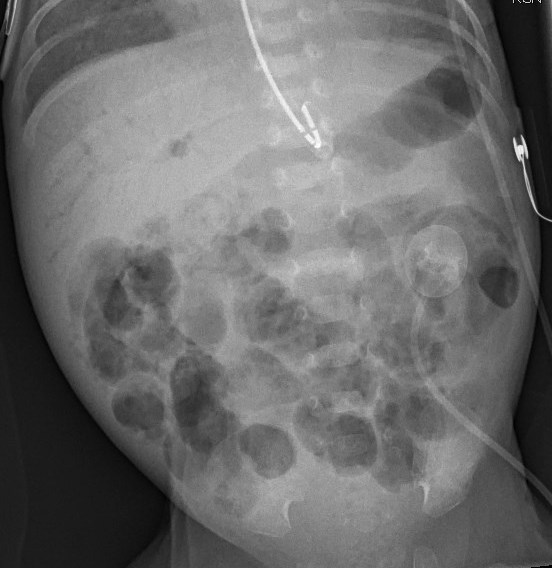

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is thought to be due to bowel wall injury or hypoxia causing inflammation and bacterial colonization of the bowel wall. The exact cause is unknown. It is predominantly a disease associated with prematurity, but full-term infants are occasionally affected (0.7 per 1000 full-term births). Typically it presents around day 3 or 4 of life in the term infant and up to day 10 in the preterm neonate.2 Risk factors include prematurity, hypoxia, maternal preeclampsia, maternal cocaine use, congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, hypotension, and acidosis. Presenting features include abdominal distention, irritability, poor feeding, vomiting, coffee grounds or bilious emesis, diarrhea, bloody stools, fever, lethargy, and shock.3 Abdominal X-rays may show pneumatosis intestinalis, portal vein or peritoneal air, bowel wall thickening, or dilated bowel loops. Ultrasonographic evaluation may reveal air/gas within the portal system and ascites. Electrolytes, CBC, and blood cultures should be obtained. Prompt surgical consultation and broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics are essential. Supportive measures include discontinuing oral feeds, placement of a nasogastric tube to decompress the stomach, and fluid resuscitation. Admission with serial abdominal X-rays is indicated.

CME Question

A 4-day-old infant presents with bloody stools and abdominal distention. Which of the following statements regarding necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is true?

- NEC only occurs in preterm infants.

- The diagnosis is typically made by ultrasound.

- Treatment includes intravenous antibiotic therapy and cessation of oral feeds.

- Abdominal X-rays are usually normal.

Start or Resume CME Test (Opens in a new Tab/Window)

Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) occurs in 2-4 per 1000 births. The incidence is 2-5 times greater in males than females, often the firstborn male. There is often a family history and Caucasian males seem to be affected more commonly. The use of macrolide antibiotics seems to be a contributing factor in some cases. Infants commonly present with non-bilious, projectile vomiting between 2-8 weeks of age. Examination of the infant is usually benign but may reveal mild dehydration. Rarely, infants will present late in the course of the disease with significant dehydration and failure to thrive. Examination of these infants may reveal visible peristalsis in the left upper quadrant and a palpable “olive” in the epigastrium, usually when the infant’s stomach is empty. Abdominal X-rays may reveal a distended stomach (See Figure: Distended Stomach in Pyloric Stenosis) sometimes with peristaltic waves, known as the “caterpillar sign.” Ultrasound is the diagnostic modality of choice in the ED.4 (See Figure: Pyloric Stenosis.) The classic laboratory finding is a hypochloremic and hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. Ultrasound is the diagnostic modality of choice.4 Muscle thickness > 3-4 mm and a pyloric channel length > 14-18 mm is suggestive of pyloric stenosis. If an upper GI series is obtained it will show delayed gastric emptying, the “string sign” of contrast passing through the narrowed pylorus, the “shoulder sign” (the hypertrophied pylorus imposed on the antrum), or a “double track line” created by contrast flowing through the pylorus.

Fluid resuscitation with normal saline in concert with surgical consultation and surgical repair provides the definitive treatment.

CME Question

A 2-week-old infant presents with projectile non-bilious vomiting. Which statement regarding radiologic imaging of pyloric stenosis is false?

- Abdominal X-rays may show a double bubble.

- Abdominal X-rays may show a distended stomach.

- Ultrasound is the diagnostic testing of choice.

- Upper GI series may show the string sign.

Start or Resume CME Test (Opens in a new Tab/Window)

National Guideline/Academic Resource

Malrotation or Midgut Volvulus

Congenital malrotation of the midgut may result in volvulus (twisting of a loop of bowel around its mesenteric attachment). Embryonically the intestine rotates 270 degrees during gestational week 5 to 8, with failure to rotate or incomplete rotation resulting in incorrect mesenteric attachment of the intestine and the risk for volvulus. Infants with malrotation may present with intermittent bilious vomiting, constipation, or failure to thrive. Bilious vomiting in the neonate should prompt urgent evaluation for this condition. The infant may be well appearing, or if the bowel is necrotic, the infant may present in shock. Hematochezia and jaundice are late signs. Abdominal X-rays may be normal or may demonstrate a duodenal obstruction or the “double bubble sign” with a stomach and duodenal bubble with a paucity of gas in the rest of the abdomen. An upper GI series is the diagnostic test of choice. In the case of volvulus, the contrast does not cross to the left side and a “corkscrew” sign may be present due to twisting of the jejunum. Dehydration and acidosis may be evident on laboratory evaluation. Rehydration with normal saline is usually necessary. A nasogastric tube to decompress the stomach should be placed and broad-spectrum antibiotics for enteric organisms (such as ampicillin and gentamicin) should be administered. Urgent surgical consultation is necessary for definitive management.

CME Question

A 2-week-old male infant presents to the ED with a 3 episodes of bilious emesis today. The infant appears ill and lethargic. The diagnostic tool of choice for diagnosing malrotation with midgut volvulus is:

- Abdominal MRI.

- Abdominal X-rays.

- Upper GI series.

- Abdominal CT.

Start or Resume CME Test (Opens in a new Tab/Window)

Constipation/Hirschsprung’s Disease

Decreased stooling or hard stools in the newborn is most commonly due to the diet of the infant. Formula-fed infants typically stool less frequently than breastfed infants. Rectal stimulation or glycerin suppositories may relieve the constipation and the associated parental anxiety.

Hirschsprung’s disease should be suspected in any infant who fails to pass meconium spontaneously by 24-48 hours after birth. Often there is abdominal distention. Delayed passing of meconium also may be due to maternal diabetes, prematurity, or cystic fibrosis.5

Diagnostic procedures used in the diagnosis of Hirschprung’s disease include:

- Contrast enema – may or may not show the characteristic transition zone in the newborn. Delayed X-rays after 24 hours may show retained contrast material.

- Rectal biopsy – This is used to confirm the diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s, absence of ganglion cells, and hypertrophied non-myelinated axons.

Surgical consultation is required for Hirschprung’s disease. Surgical options include a primary pull-through procedure or a temporary colostomy once the infant is stablized. The infant often remains at risk for constipation, encopresis, and enterocolitis throughout life.

CME Question

The mother of a 1-month-old infant complains of vomiting and abdominal distention in the infant for 1 day. The birth history is significant for the delayed passage of meconium. True statements regarding Hirshsprung’s disease are:

- A rectal biopsy showing the absence of ganglion cells confirms the diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease.

- Enterocolitis, constipation, and encopresis are possible, even after surgical correction.

- A contrast enema may show the transition zone.

- Abdominal distention and constipation may be relieved by rectal stimulation or glycerin suppositories.

- All of the above.

Start or Resume CME Test (Opens in a new Tab/Window)

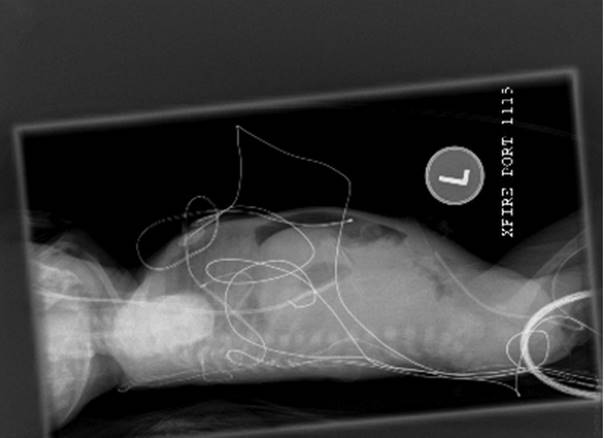

Incarcerated Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernias result from incomplete obliteration of the processus vaginalis during embryology. Bowel, peritoneal, and scrotal contents, including the testes or ovaries, may enter the inguinal canal and become trapped, resulting in incarceration and strangulation. The prevalence of inguinal hernias is as high as 4.4% and even more frequent in males (male to female ratio of 3:1 to 6:1). Females, however, have a higher rate of incarceration. Overall, the rate of incarceration for all inguinal hernias in the pediatric age group is 6-18 %.6 The infant typically presents with swelling in the inguinal area. (See Figure: Hernia) An infant with an incarcerated hernia may present with irritability, vomiting, abdominal distention, and decreased stools. Late signs of a strangulated hernia include bloody stools, lethargy, abdominal distension, and fever. An infant with an inguinal hernia, which is easily reduced, may be discharged with outpatient surgical follow-up. A hernia mass that is not easily reduced may require relaxation by non-pharmacological methods or by procedural sedation. The infant is placed in the Trendelenburg position and firm steady manual pressure applied to the hernia mass to guide it through the external inguinal ring. An urgent surgical consultation is necessary for a hernia mass that cannot be reduced or a suspected strangulated hernia. Diagnostic studies include abdominal X-rays, which may reveal air-fluid levels and free air if perforation is present. (See Figure: Free Air in Abdomen). An ultrasound will help to distinguish a hernia mass from hydrocele, testicular pathology, tumor mass, or abscess. If bowel necrosis is suspected, the infant should be made NPO and referred to surgical consultation immediately.

CME Question

A 1-month-old male infant comes to the ED with a history of inguinal swelling and vomiting. Examination of the infant reveals right inguinal swelling, which is tense and tender and not easily reduced with manipulation. True statements regarding an incarcerated inguinal hernia are:

- Female infants are more commonly affected.

- Testes or ovaries may be entrapped in the hernia.

- Bloody stools are an early sign of strangulation.

- Ultrasound of the scrotum in a male patient does not help to establish the diagnosis.

Start or Resume CME Test (Opens in a new Tab/Window)

Jaundice

Jaundice is the yellowish discoloration of the skin and or sclera due to bilirubin deposition. In the newborn, jaundice is visible at about bilirubin levels > 5 g/dL. Approximately 85% of term newborns and the majority of premature neonates develop clinical jaundice. The main source of bilirubin is from the breakdown of hemoglobin. Physiologic jaundice occurs in many newborns with a peak bilirubin level of about 12 mg/dL peaking at day 3 to 5. Premature infants usually peak around day 5. Non-physiologic jaundice is characterized by certain factors such as bilirubin increase at a rate of greater than 5 mg/dL/24hr. Risk factors include low birth weight, prematurity, and breastfeeding. The CDC utilizes the following acronym for these risk factors:4

J Jaundice in the first day of life

A a sibling with neonatal jaundice

U unrecognized hemolysis such as ABO or Rh incompatibility

N non-optimal feeding

D deficiency in G6PD or genetic disorder

I infection

C cephalhematoma or bruising

E East Asian or Mediterranean descent

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia can cause bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND) when unconjugated bilirubin crosses the blood-brain barrier and binds to the tissue of the brain. The long-term effects are referred to as kernicterus. The goal of treatment is to prevent the neurologic sequelae. Several factors have contributed to the decrease in the incidence of kernicterus since the 1970s, most notable are the administration of Rh immunoglobulin (Rhogam) to mothers who are Rh negative, thereby decreasing the incidence of neonatal Rh hemolytic disease, and the introduction of phototherapy for the treatment of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

In 2004, the American Academy of Pediatrics subcommittee on hyperbilirubinemia provided guidelines for the identification and treatment of infants at risk for severe hyperbilirubinemia with phototherapy. The guidelines pertained to infants > 35 weeks gestational age.1 The recommendations include promotion of successful breastfeeding, performing a risk assessment for severe hyperbilirubinemia prior to discharge, providing early follow-up and when indicated, and treatment of newborns with phototherapy or exchange transfusion to prevent BIND and long-term sequelae of kernicterus.

Therapeutic measures utilized in treating hyperbilirubinemia include phototherapy, exchange transfusion, and optimizing breastfeeding while also providing supplemental formula if necessary. The guidelines for the initiation of phototherapy are based on the hour-specific total bilirubin level, gestational age, and the presence of certain risk factors. The risk factors include the presence of isoimmune hemolytic disease, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, asphyxia, serum albumin levels < 3g/dl, lethargy, temperature instability, acidosis, and sepsis.

If total serum bilirubin is approaching or above the level at which phototherapy is indicated, additional laboratory evaluation may include direct bilirubin level, CBC to check for polycythemia or anemia from hemolysis, cord blood results for indirect Coombs and maternal blood type and Rh, infant’s for blood type and Rh and direct Coombs, peripheral smear for RBC morphology (may detect hereditary spherocytosis), reticulocyte count, and G6PD screen if African, Asian, or Mediterranean descent. Testing for liver disease, TORCH infections, metabolic disease, or sepsis may be indicated as well, particularly when there is prolonged jaundice or increased levels of direct bilirubin.

The general guidelines for initiation of phototherapy and exchange transfusion are based on the gestational age, level of bilirubin, and presence of risk factors.7,8 Exchange transfusion is a method of removing bilirubin from the circulation when the infant has signs of neurologic dysfunction and aggressive phototherapy is inadequate.

National Guideline/Academic Resource

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/114/1/297.full

CME Question

A 3-day-old infant presents to the ED with jaundice of the skin and eyes. The infant was born at term with no complications. The following are true statements regarding the AAP guidelines for the identification and treatment of infants at risk for severe hyperbilirubinemia:

- The guidelines are for infants over 322 weeks.

- Breast feeding should be optimized.

- High risk infants should be sent home on phototherapy.

- Treatment with phototherapy and or exchange transfusion do not prevent kernicterus.

Start or Resume CME Test (Opens in a new Tab/Window)

Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

This is the presence of direct bilirubin > 2 mg/dL and > 10% of total serum bilirubin. Causes of direct hyperbilirubinemia include hyperalimentation, biliary obstruction or atresia, choledochal cyst, hepatitis, sepsis, alpha1 antitrypsin deficiency, hemoglobinopathies, cystic fibrosis, hypothyroidism and inborn errors of metabolism. These infants should be admitted and investigations done to find the etiology.

CME Question

A 4-week-old infant is referred to the ED by the pediatrician because of persistent jaundice. The total bilirubin is 13 mg/dl and the direct bilirubin level is 6 mg/dl. The following statements are true regarding the definition of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia:

- The direct bilirubin is > 50% of the total serum bilirubin.

- The level of direct bilirubin is > 1.5 mg/dl.

- Causes include sepsis, hypothyroidism and hemoglobinopathies.

- Outpatient investigations and management is recommended.

Gastrointestinal Emergencies References

- Poets CF. Gastroesophageal reflux: a critical review of its role in preterm infants.Pediatrics 2004;113(2)e128-e132.

- Louie JP. Essential diagnosis of abdominal emergencies in the first year of life. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25(4):10091040.

- Hostetler MA, Schuman M. Necrotizing enterocolitis presenting in the Emergency Department: case report and review of differential considerations for vomiting in the neonate. J Emerg Med.2001;21(2):165-170.

- Vasarada P. Ultrasound evaluation of acute abdominal emergencies in infant and children. Radiol Clin North Am 2004; 42(2):445-456.

- Kessmann J. Hirschsprung disease:diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(8):1319-1322.

- Cantor, R. M., & Sadowitz, P. D. (2010). Gastrointestinal emergencies. In Neonatal emergencies (pp. 110-111). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). CDC - Jaundice and Kernicterus, HCP - NCBDDD. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/jaundice/hcp.html.

- American academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia, Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 weeks or more gestation. Pediatrics 2004;114:297-316.