HICprevent

This award-winning blog supplements the articles in Hospital Infection Control & Prevention.

‘It’s Alive’: Scabies Gets Under Your Skin

August 31st, 2023

By Gary Evans, Medical Writer

Healthcare workers have seen and suffered seemingly everything, but there is one creature as unnerving as the ragged screech of fingernails across a chalkboard: Sarcoptes scabiei hominis.

Imagine a parasite crawling beneath your skin, consuming blood, laying eggs, leaving its byproducts, spreading to sensitive areas of the body, and creating serpentine, visible burrowing lines. The psychological aspects can be intense, troubling the mind with a singular thought: “It’s alive.”

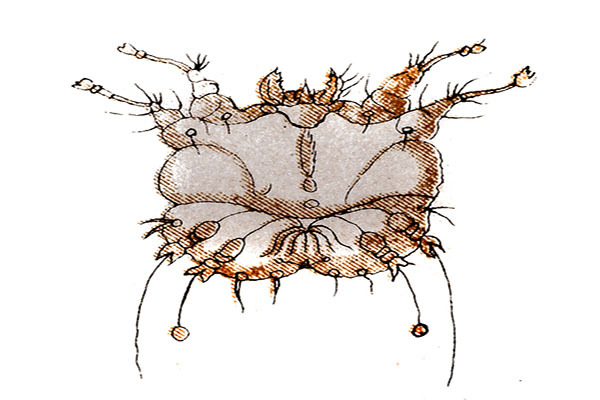

It’s probably for the best that without a microscope or possibly a strong magnifying glass you cannot see the transmissible mite scabies. Upon magnification you see a mite from class Arachnida. Yes, a cousin of the spider, with eight legs to prove it. Often misdiagnosed as other skin conditions, scabies can spread via skin-to-skin contact from infested patients to healthcare workers. The mites commonly infest areas like the webbing between the fingers, skin folds in elbows and knees, and the area surrounding the nipples, male genitalia and the lower buttocks. Infested individuals can spread the mite to different sites on their own bodies through scratching that is said to be very difficult to resist.

The cycle begins when a pregnant mite burrows beneath the skin, consuming blood and laying her eggs. The resulting adult mites can live anywhere from a month to six weeks. The first reaction in the host is primarily allergic, as the body responds to the presence of multiplying scabies, and rash and skin disruptions appear. This results in the intense itching that can lead to physical and mental detriments.

“So this is really critical when thinking about the incubation period [six weeks] for scabies within the host,” said Taylor Keck, MPH, CIC, an infection preventionist, at UPMC Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh. “Transmission occurs through close person-to-person contact and less often, from fomite-to-person contact, so think of clothing or shared bedding, things like that.”

Keck described an outbreak of scabies recently in Orlando at the 2023 conference of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC). She also coauthored a recently published paper on the outbreak, in which an undiagnosed patient exposed 46 healthcare workers in a “hands-on” rehabilitation unit.

Scabies can contribute to depression and declining quality of life, partly because of the old myth that it is caused by a lack of hygiene and the fact that it can be sexually transmitted. However, the primary contributor to spread is living in crowded conditions, where skin contact may occur or common fomites and bed linens may spread scabies to family members or co-inhabitants.

“All units were followed for the 6 weeks [incubation period] since diagnosis of the index patient,” the authors reported. “A total 20 nurses and 26 physical therapists were exposed. Twenty-nine presented with symptoms and were treated with ivermectin and permethrin or only ivermectin.”

The problem was the patient had been hospitalized for more than a week with multiple morbidities, including an undiagnosed skin rash. After being treated with steroids that undermined immunity, the patient had the dramatic appearance of “crusted” or Norwegian scabies. The patient was put in contact isolation with an emphasis on glove use, but transmission had already occurred to many healthcare workers.

“These healthcare workers had visible rashes and other suspicious indications for disease,” Keck said. “So they were really complaining of this horrible rash, itchiness.”

In addition to the symptomatic workers who were treated, there were more than a dozen staff who reported contact with the patient but never developed symptoms.

“We definitely had a high anxiety situation going on,” she said. “We had healthcare workers that had nothing visible, they complained of a little itching, or they had one spot [of concern].”

Two of these workers expressed enough angst and anxiety that their requests for treatment were granted.

“There really wasn’t any concern that anything was a brewing with them,” Keck said. “We talked about that high anxiety of staff. I cannot say that enough. They really just kept circling back. We weren’t visually seeing anything of concern, but they really just wanted that treatment. They wanted that ivermectin because it gives you that long-term coverage.”

Anxiety is often seen with scabies, given disrupted sleep due to constant itching and the uneasy awareness that the body has been invaded by a living, moving parasite. The term “scabiophobia” has been coined to describe those with an extreme, irrational fear of the mites.

“Scabies morbidity could be linked to both clinical pathology and emotional elements of the disease” researchers report. “It should be kept in mind that patients diagnosed with scabies are affected not only clinically but also emotionally, and they can be consulted to psychiatry departments when necessary.”

All healthcare workers in the outbreak were cleared of infestation and none spread scabies to their families.

For more on this story, see the next issue of Hospital Employee Health.

Gary Evans, BA, MA, has written numerous articles on infectious disease threats to both patients and healthcare workers for more than three decades. These include stories on healthcare-associated infections like MRSA, C. diff and a panoply of emerging multidrug resistant gram negative bacteria and fungi like Candida auris. In an era of pandemic pathogens, he has covered HIV, SARS, pandemic influenza, MERS, Ebola and SARS-CoV-2. Evans has been honored for excellence in analytical reporting five times by the National Press Club in Washington, DC.