Achieving Successful Rehabilitation in the ICU

October 1, 2015

Reprints

By Kathryn Radigan, MD, MSc

Assistant Professor, Pulmonary Medicine, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago

Dr. Radigan reports no financial relationships relevant to this field of study.

Almost 50% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients with sepsis, multi-organ failure, or prolonged respiratory failure exhibit protracted muscular weakness during their critical illness that often persists after hospital discharge.1 In a study that examined consecutive ICU patients without preexisting neuromuscular disease who underwent mechanical ventilation for 7 or more days, the prevalence of ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) was 25.3%.2 Profound weakness may affect any muscle group, including the diaphragm. In one study that examined brain-dead organ donors undergoing mechanical ventilation, the diaphragm showed marked atrophy of both slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibers within hours of inactivity.3 Patients who develop ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) require a longer duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay and suffer significant long-term physical, mental, and financial sequelae.4 Herridge et al showed that even relatively young survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome demonstrated persistent subjective weakness, exercise limitation, and reduced physical quality of life 5 years after their critical illness.5

DIAGNOSIS

ICU-AW may be neuropathic or myopathic, often with considerable overlap. Clinicians should consider ICU-AW in almost every critically ill patient who is ventilated and especially in those with failure to wean from the ventilator. Signs of critical illness myopathy include proximal and distal muscle weakness and decreased reflexes with normal sensation. Critical illness polyneuropathy presents with limb muscle weakness and atrophy, reduced or absent deep tendon reflexes, loss of peripheral sensation to light touch and pin prick, and relative preservation of cranial nerve function. Electromyography, nerve conduction studies, and consultation with a neurologist may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis.

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Many factors may contribute to the risk of ICU-AW. There is a strong relationship between ICU length of stay (LOS) and poor physical outcomes. Implementing existing evidence-based strategies to reduce ICU LOS and associated bed rest may be the best preventive measures for improving patient outcomes. Although there is still significant controversy whether other specific treatment strategies (e.g., minimizing corticosteroids, control of severe hyperglycemia, avoidance of paralytics) affect physical outcomes in the ICU, it is always better to err on the side of caution and modify these risks whenever possible.6,7

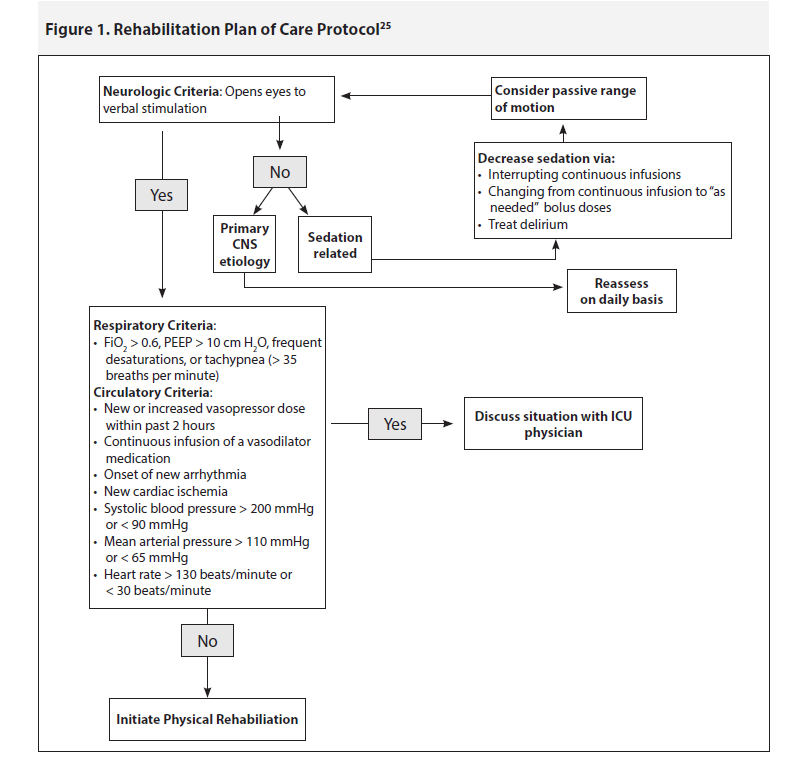

Physical therapy during critical illness has proven to mitigate many of the potential complications of critical illness. Historically, it has been standard of care for critically ill patients to be placed on bed rest, often in a medication-induced coma. More recently, it is becoming common to see ventilated patients not just receiving physical therapy but even taking laps around the unit. Patients usually start with sitting up at the side of the bed and then progress stepwise to dangling legs over the side of the bed, standing, transferring to a chair, and ultimately walking. Physical therapy within the ICU is associated with improved walking ability at discharge, improved respiratory and overall muscle strength, increased ability to perform activities of daily living at discharge, and improved health-related quality of life (i.e., higher number of patients with independent functional status and improved SF-36 physical functioning scores).8-15 Rehabilitation within the ICU has also been shown to shorten ICU and hospital LOS, increase number of discharges home, and improve 1-year mortality.8,13,14,16,17 Theoretically, physical rehabilitation may also lead to improved interdisciplinary communication as it requires daily coordination with the physician team (assessment of appropriateness for therapy), nursing (minimizing sedation in advance of physical therapy), respiratory therapists (maintenance of the airway and effective ventilation during therapy), and the physical therapy team. This coordinated effort often leads to reduced need for sedation and physical restraints. Patients’ family members often positively perceive improved team communication, which would be predicted to improve patient and family satisfaction. Furthermore, implementation of physical therapy is safe, with a reported incidence of adverse outcomes < 1% in careful trials, none of which are severe.13,16,18-20 To decrease the risk of adverse events, every institution should have a plan of care protocol (see Figure 1).

Early mobilization during ICU admission is a key aspect to implementing an ICU physical therapy program. A randomized, controlled trial at two university hospitals showed that interruption of sedation along with physical and occupational therapy during mechanical ventilation, as opposed to initiation of therapy after discontinuation of mechanical ventilation, resulted in better functional outcomes at hospital discharge, a shorter duration of delirium, and more ventilator-free days compared with standard care.7 Despite receiving the same amount of daily physical therapy after mechanical ventilation, the intervention group received an average of 19 minutes of physical therapy per day during mechanical ventilation while the control group received no physical therapy until after extubation.8 This study demonstrated that the benefits of physical and occupational therapy occur while patients are receiving mechanical ventilation, a time in which many medical centers defer physical therapy.

CULTURE CHANGE

Unfortunately, improving weakness in our ICU patients is not as simple as the implementation of physical therapy. Ideally, each ICU should have a mobility team that includes a physical therapist to assess and treat, a nurse to assist in physiologic stability, and a respiratory therapist who is responsible for airway and ventilator management. The critical care physician should also be involved to assure there are no clinical contraindications to physical activity and recommend changes in mechanical ventilator settings during exercise. To be successful with mobility, most ICUs need to go through a culture change. The ABCDE Initiative outlines straightforward tenets to enable success with this culture change. The ABCDE bundle includes implementing the Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium monitoring/management, and Early exercise/mobility bundle into everyday practice.21 This initiative promotes effective physical therapy as it encourages treatment of delirium and limitation of sedative medications. An 18-month prospective, before-after study of 146 pre-bundle and 150 post-ABCDE bundle patients examined the effectiveness and safety of this initiative. Investigators were aggressive with daily physical therapy when patients met pre-specified criteria with exceptions permitted only by a specific order. Patients who underwent the ABCDE bundle spent 3 more days breathing without mechanical ventilation, experienced less delirium, and increased their odds of mobilizing out of bed at least daily compared to pre-bundle patients. Although this initiative stressed the importance of patients being awake, it has also been shown that passive range of motion and bedside ergometer (along with active exercise training when the patient is able to participate) enhanced recovery of functional exercise capacity, self-perceived functional status, and muscle force at hospital discharge.10

To successfully change cultural practice, it is also paramount to understand the specific barriers to a project in order to design the correct intervention. Needham et al developed the 4 Es model, which promotes Engagement, Education, Execution, and Evaluation to overcome barriers within their ICU physical therapy program.13 Engaging the group meant convening regularly scheduled interdisciplinary meetings, providing information and updates on the project with MICU and hospital-wide newsletters, designing informational posters, conducting didactic conferences and presentations, and inviting ICU survivors who participated in rehabilitation to share their stories. Patient experiences emphasized the importance of decreased sedation and early rehabilitation. Education was the next important aspect of the process and included meetings, presentations addressing long-term complications of critical illness, and benefits of physical and occupational therapy, including 16 educational sessions to inform all MICU nurses regarding sedation-related issues that may dictate the effectiveness of physical therapy. Execution included various measures to modify standardized admission orders, encourage culture change with sedation practices, develop safety guidelines, change staffing, and encourage consultations with physiatrists and neurologists (see Table 1). Finally, evaluation of the project occurred on an ongoing, regular basis to discuss progress, barriers, and solutions.

IMPLEMENTING PHYSICAL THERAPY IN THE ICU

What if your hospital doesn’t have physical therapy in the ICU? Take ownership and make it happen. Appeal to the financial senses of your institution with data. Rehabilitation within the ICU shortens ICU and hospital LOS, increases the number of discharges home, and improves 1-year mortality.8,13,14,16,17 These improvements are associated with significant cost savings. Needham et al evaluated the potential annual net cost savings of implementing their own early rehabilitation program. This data set is available in easily adaptable spreadsheets to adjust to the needs of hospitals with 200, 600, 900, and 2000 annual admissions, accounting for both conservative and best-case scenarios. For example, they calculated a net cost savings of more than $800,000 generated in a scenario of 900 annual admissions with actual LOS reductions of 22% and 19% for the ICU and floor, respectively. They were able to show that investment in an ICU early rehabilitation program can generate net financial savings for U.S. hospitals.22 Needham et al have published an Excel model that can assist in conducting such financial analyses customized to a hospital’s unique situation.23

CONCLUSION

Survivors of critical illness suffer from physical disabilities for at least 5 years after their initial illness.5 Clinicians should consider ICU-acquired weakness in almost every critically ill patient who is ventilated but especially those with failure to wean from the ventilator. Early physical therapy is a crucial intervention to both prevent and treat ICU-acquired weakness. Appealing to the financial senses of your institution to implement physical therapy in the ICU may be crucial to improve ICU patient outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Stevens RD, et al. Neuromuscular dysfunction acquired in critical illness: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:1876-1891.

- De Jonghe, et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: A prospective multicenter study. JAMA 2002;288:2859-2867.

- Levine S, et al. Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1327-1335.

- De Jonghe B, et al. Does ICU-acquired paresis lengthen weaning from mechanical ventilation? Intensive Care Med 2004;30:1117-1121.

- Herridge MS, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1293-1304.

- Needham DM, et al. Risk factors for physical impairment after acute lung injury in a national, multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:1214-1224.

- Fan E, et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: A two-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med 2014;42:849-859.

- Schweickert WD, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:1874-1882.

- Nava S. Rehabilitation of patients admitted to a respiratory intensive care unit. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:849-854.

- Burtin C, et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2499-2505.

- Porta R, et al. Supported arm training in patients recently weaned from mechanical ventilation. Chest 2005;128:2511-2520.

- Chiang LL, et al. Effects of physical training on functional status in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Phys Ther 2006;86:1271-1281.

- Needham DM, et al. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: A quality improvement project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91:536-542.

- Chen SY, et al. Physical training is beneficial to functional status and survival in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. J Formos Med Assoc 2011;110:572-579.

- Chen YH, et al. Effects of exercise training on pulmonary mechanics and functional status in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Resp Care 2012;57:727-734.

- Morris PE, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2238-2243.

- Malkoc M, et al. The effect of physiotherapy on ventilatory dependency and the length of stay in an intensive care unit. Int J Rehabil Res 2009;32:85-88.

- Clini EM, et al. Functional recovery following physical training in tracheotomized and chronically ventilated patients. Respir Care 2011;56:306-313.

- Bailey P, et al. Early activity is feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Crit Care Med 2007;35:139-145.

- Zanni JM, et al. Rehabilitation therapy and outcomes in acute respiratory failure: An observational pilot project. J Crit Care 2010;25:254-262.

- Balas MC, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1024-1036.

- Lord RK, et al. ICU early physical rehabilitation programs: Financial modeling of cost savings. Crit Care Med 2013;41:717-724.

- OACIS: Clinical Programs and Quality Improvement Projects. 2015. Available at http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/pulmonary/research/outcomes_after_critical_illness_surgery/oacis_programs_qi_projects.html. Accessed Sept. 1, 2015.

- Needham DM, Korupolu R. Rehabilitation quality improvement in an intensive care unit setting: Implementation of a quality improvement model. Top Stroke Rehabil 2010;17:271-281.

Table 1. Steps to Ensure Culture Change22 |

|

Clinicians should consider ICU-acquired weakness in almost every critically ill patient who is ventilated.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.